⚠️ Affiliate Disclaimer: This post may contain affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you, if you make a purchase through one of these links. I only recommend products or services I genuinely trust and believe can provide value. Thank you for supporting My Medical Muse!

How Blood Sugar Is Regulated in the Body: 10 Key Mechanisms Explained

Blood sugar doesn’t fluctuate randomly, it is tightly monitored and controlled by multiple organs working in precise coordination. Too little glucose and the brain struggles, too much and tissues are gradually damaged. Diabetes is not a sudden surprise, it is the predictable result of specific regulatory failures.

This article breaks down how blood sugar is normally controlled, step by step, and what fails in diabetes, with a focus on biology and physiology rather than oversimplification or motivational advice.

Why Blood Sugar Control Matters

Glucose serves as the primary metabolic fuel for several vital tissues in the body. The brain relies almost exclusively on glucose under normal conditions and has very limited capacity to store it. Red blood cells are entirely dependent on glucose because they lack mitochondria and cannot metabolize fatty acids. Additionally, regions of the renal medulla, peripheral nerves, and certain parts of the central nervous system also require a continuous glucose supply to maintain normal function.

While glucose is essential, excess circulating glucose is toxic, persistent hyperglycemia initiates a cascade of harmful biochemical processes. Proteins undergo non-enzymatic glycation, which disrupts their structure and function. Oxidative stress increases, damaging cellular components. Endothelial dysfunction impairs vascular health, while low-grade inflammation and progressive fibrosis gradually compromise organ systems. Collectively, these mechanisms underlie the development of both microvascular complications (such as retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy) and macrovascular complications (including atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease) in diabetes.

Because both hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia are dangerous, the body maintains blood glucose within a very narrow range, approximately 70 to 100 mg/dL during fasting in healthy individuals. Achieving this requires a precisely tuned, continuous feedback system involving multiple hormones, neural signaling pathways, and coordinated organ responses. Glucose homeostasis is not simply a matter of conscious control, dietary choices, or willpower, it is a physiological system operating largely beyond voluntary influence.

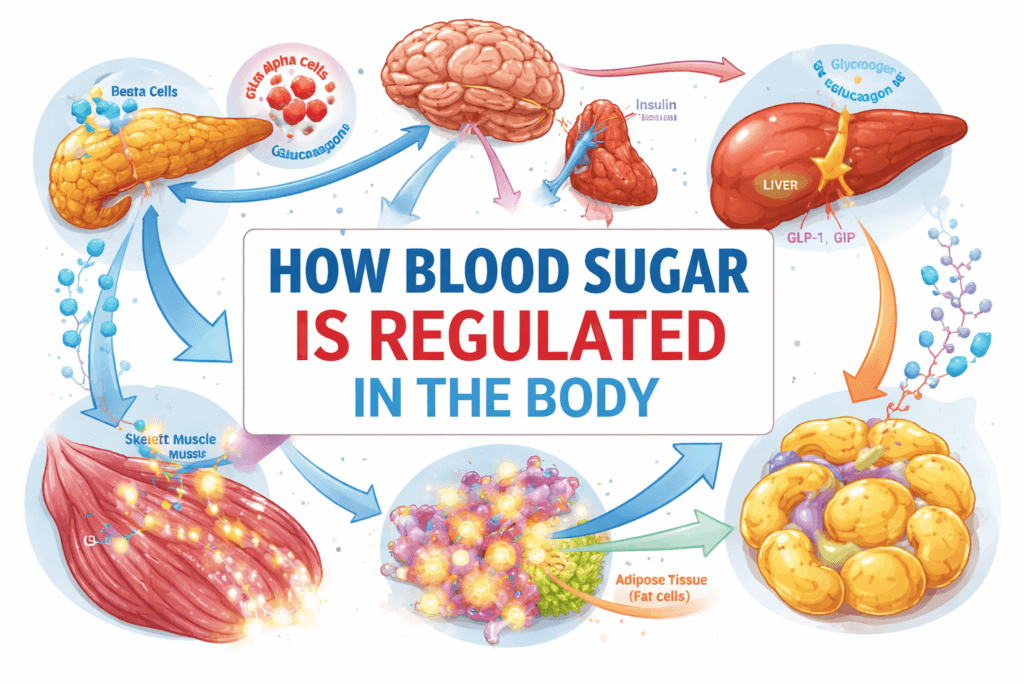

The Core Organs of Glucose Regulation

Blood sugar regulation is an integrated, multi-organ process. Each organ contributes specific functions, and disruption in any component can destabilize the entire system:

- Pancreas: Serves as the primary glucose sensor and hormonal regulator. It secretes insulin to lower blood glucose and glucagon to raise it, maintaining dynamic equilibrium.

- Liver: Acts as a buffer and reservoir for glucose, absorbing excess post-meal glucose and releasing glucose during fasting to maintain consistent systemic levels.

- Skeletal Muscle: Functions as the main site for post-prandial glucose disposal. Muscle tissue takes up glucose for energy use or glycogen storage, significantly influencing circulating glucose levels.

- Adipose Tissue: Stores excess energy as fat and secretes hormones (adipokines) that modulate insulin sensitivity in muscle and liver. Dysfunctional adipose tissue can exacerbate insulin resistance and systemic hyperglycemia.

- Gastrointestinal Tract: Regulates glucose entry into the bloodstream and secretes incretin hormones, which enhance insulin secretion in response to meals and help coordinate post-prandial glucose control.

- Brain and Autonomic Nervous System: Monitor glucose continuously and coordinate counter-regulatory responses, such as stimulating hepatic glucose release and modulating hormone secretion during hypoglycemia.

Diabetes typically develops when multiple components of this network fail simultaneously or sequentially. As the compensatory capacity of the system is exceeded, blood glucose control becomes increasingly unstable, eventually leading to persistent hyperglycemia and its associated complications.

The Pancreas: Central Sensor and Hormonal Controller

Beta Cells and Insulin Secretion

The pancreas contains clusters of endocrine cells called the islets of Langerhans, with beta cells acting as precise glucose sensors. Beta cells continuously monitor blood glucose levels and adjust insulin secretion in real time to match physiological needs.

When glucose rises, it enters beta cells through GLUT2 transporters, which allow glucose to flow proportionally to its plasma concentration, making them ideal for sensing. Once inside the cell, glucose undergoes metabolism, increasing intracellular ATP levels. Rising ATP closes ATP-sensitive potassium channels, causing the cell membrane to depolarize. This depolarization opens voltage-gated calcium channels, allowing calcium influx, which triggers the exocytosis of insulin-containing granules into the bloodstream.

This process occurs rapidly, within minutes, and insulin secretion is finely graded according to both the magnitude and rate of glucose increase. This ensures that glucose is cleared efficiently without overshooting, maintaining homeostasis.

Alpha Cells and Glucagon

Adjacent alpha cells within the islets secrete glucagon, a hormone that raises blood glucose primarily by stimulating hepatic glycogen breakdown and gluconeogenesis. In healthy individuals, insulin and glucagon operate in a reciprocal manner, high blood glucose triggers insulin release and suppresses glucagon, while low glucose inhibits insulin and promotes glucagon secretion.

This tight balance allows the body to maintain stable glucose levels during fasting, feeding, and variable energy demands. In diabetes, this balance is disrupted. Beta-cell dysfunction reduces insulin secretion, and glucagon is often inappropriately elevated, leading to excessive hepatic glucose production and contributing to hyperglycemia.

Insulin: Its True Biological Role

Insulin is often simplistically described as a hormone that lowers blood sugar. This characterization is incomplete and can be misleading, in reality, insulin is a fundamental anabolic signal that communicates energy availability to tissues and orchestrates metabolic priorities throughout the body. Its role extends far beyond glucose disposal.

In skeletal muscle, insulin promotes glucose uptake by triggering the translocation of GLUT4 transporters to the cell membrane. This allows glucose to enter muscle cells efficiently. Insulin also stimulates glycogen synthesis, converting glucose into stored energy, and supports protein synthesis. Skeletal muscle accounts for the majority of insulin-mediated glucose disposal after meals, making its responsiveness critical for post-prandial glucose control.

In adipose tissue, insulin suppresses lipolysis, preventing excessive release of free fatty acids into circulation. It promotes triglyceride storage and facilitates glucose uptake for lipid synthesis. These processes prevent the accumulation of circulating fatty acids, which can impair insulin signaling in other tissues such as the liver and muscle.

In the liver, insulin restrains glucose production rather than directly increasing uptake. It suppresses gluconeogenesis, inhibits glycogen breakdown, and promotes glycogen storage. By controlling hepatic glucose output, insulin prevents fasting and post-absorptive hyperglycemia.

Insulin does not force glucose into cells indiscriminately, it modifies cellular signaling pathways, enzyme activities, and gene expression, shifting metabolism toward energy storage and utilization according to the body’s nutritional state.

The Liver: Buffer, Reservoir, and Gatekeeper

The liver serves as the central buffer between dietary glucose intake and systemic circulation. Its ability to absorb, store, produce, and release glucose depending on metabolic demands is crucial for maintaining glucose stability.

After a meal, rising insulin levels signal the liver to take up excess glucose and convert it into glycogen for storage. When glycogen stores reach capacity, surplus glucose is redirected into fatty acid synthesis for long-term energy storage.

During fasting or between meals, declining insulin and rising glucagon trigger the liver to release glucose. Initially, this occurs via glycogenolysis, the breakdown of stored glycogen. As fasting continues, gluconeogenesis becomes the dominant source, synthesizing glucose from lactate, glycerol, and amino acids.

In diabetes, hepatic insulin resistance is common. The liver fails to suppress glucose production even in the presence of elevated circulating glucose, contributing significantly to fasting and post-absorptive hyperglycemia and complicating glycemic control.

Skeletal Muscle: The Primary Site of Glucose Disposal

Skeletal muscle is responsible for approximately 70-80% of post-meal glucose uptake, making it the primary site for glucose clearance. Uptake depends both on insulin signaling and muscle contraction.

Insulin stimulates GLUT4 translocation to the muscle cell membrane, enabling glucose entry. Muscle contraction also activates GLUT4 independently of insulin, which is why physical activity improves glucose control even in states of insulin resistance.

When insulin resistance develops, intracellular signaling downstream of the insulin receptor is impaired. GLUT4 translocation is reduced, glucose uptake diminishes, and circulating glucose remains elevated. This defect is central to post-prandial hyperglycemia, the characteristic spikes seen after meals in type 2 diabetes.

Adipose Tissue: Active Metabolic Regulator

Adipose tissue is not merely an energy storage depot, it is a highly active endocrine organ influencing systemic metabolism.

Healthy adipose tissue safely stores surplus energy and secretes adipokines that enhance insulin sensitivity in muscle and liver. Dysfunctional adipose tissue, particularly visceral fat, releases excessive free fatty acids and pro-inflammatory cytokines. These substances impair insulin signaling in muscle and liver and stimulate hepatic glucose production, worsening hyperglycemia.

Visceral fat is especially impactful because it drains directly into the portal vein, delivering metabolites and inflammatory signals straight to the liver. This direct connection magnifies its effect on hepatic glucose output and systemic insulin resistance.

The Gut: Glucose Entry and Incretin Signaling

After a meal, glucose is absorbed from the small intestine into the bloodstream, raising blood glucose levels. Simultaneously, the gut secretes hormones that amplify insulin secretion in a process known as the incretin effect.

The two primary incretin hormones are glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP). These hormones have several critical actions, they enhance insulin release in response to rising glucose, suppress glucagon secretion to limit unnecessary hepatic glucose production, slow gastric emptying to moderate the rate of glucose absorption, and promote satiety, thereby influencing both acute and long-term energy balance.

In type 2 diabetes, the incretin effect is impaired, GLP-1 and GIP responses are diminished, leading to insufficient insulin secretion after meals and inappropriate glucagon activity. This contributes directly to post-prandial hyperglycemia and complicates glycemic management.

The Brain and Counter-Regulatory Control

The brain continuously monitors blood glucose levels and orchestrates counter-regulatory responses when glucose falls. During hypoglycemia, the autonomic nervous system activates, prompting the release of hormones such as adrenaline (epinephrine), cortisol, and growth hormone. These hormones increase hepatic glucose production, reduce peripheral glucose uptake, and mobilize energy stores to restore normoglycemia.

In individuals with long-standing diabetes, particularly those receiving insulin therapy, these counter-regulatory mechanisms may become blunted. This impaired hypoglycemia awareness increases the risk of severe hypoglycemia, making glucose management more precarious.

What Fails in Diabetes

Diabetes is fundamentally a disorder of glucose regulation, but the underlying failures differ between type 1 and type 2 disease:

Type 1 Diabetes

Type 1 diabetes results from autoimmune destruction of pancreatic beta cells, causing absolute insulin deficiency. Without insulin, glucose cannot enter insulin-dependent tissues, hepatic glucose production proceeds unchecked, lipolysis accelerates, and ketone production increases. Exogenous insulin is essential for survival, without it, metabolic control collapses completely.

Type 2 Diabetes

Type 2 diabetes is multifactorial and progressive, key defects include:

- Insulin resistance in muscle and liver, reducing glucose disposal and increasing hepatic glucose output

- Beta-cell dysfunction, initially compensated by hyperinsulinemia, but ultimately leading to declining insulin secretion

- Excess hepatic glucose production due to inappropriate gluconeogenesis

- Impaired incretin signaling, reducing post-meal insulin secretion and allowing excessive glucagon activity

- Adipose tissue inflammation, releasing free fatty acids and cytokines that worsen systemic insulin resistance

Diabetes emerges when these compensatory mechanisms are exhausted, resulting in sustained hyperglycemia and progressive metabolic dysregulation.

Bottom Line

Blood sugar regulation is a highly precise system, not a test of willpower or discipline. Diabetes arises when insulin action falters, insulin secretion declines, and counter-regulatory mechanisms overwhelm normal control. The body does not fail randomly; it compensates repeatedly until its defenses are exhausted.

Recognizing exactly how glucose regulation works and where it breaks down is the first step toward effective, rational treatment, early intervention, and realistic expectations for managing the disease.

🌿 Your Health, Personalized

Take control of your wellbeing. Our licensed doctors at MuseCare Consult provide private, tailored guidance for your unique health needs.

✅ Book Your ConsultationAlso Read:

- Diabetes Mellitus: 10 Essential Insights on Causes, Types, Symptoms, Complications, and Modern Management

- 10 Proven Benefits of Nutritional Counseling for Diabetes Management

- Can Intermittent Fasting Help Type 2 Diabetes? 9 Powerful Facts

- 10 Sneaky Symptoms of Prediabetes in Women Over 40 You Can’t Ignore

- 7 Surprising Reasons Why Your Blood Sugar Spikes After Eating Healthy Foods

Dr. Ijasusi Bamidele, MBBS (Binzhou Medical University, China), is a medical doctor with 5 years of clinical experience and founder of MyMedicalMuse.com, a subsidiary of Delimann Limited. As a health content writer for audiences in the USA, Canada, and Europe, Dr. Ijasusi helps readers understand complex health conditions, recognize why they have certain symptoms, and apply practical lifestyle modifications to improve well-being