⚠️ Affiliate Disclaimer: This post may contain affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you, if you make a purchase through one of these links. I only recommend products or services I genuinely trust and believe can provide value. Thank you for supporting My Medical Muse!

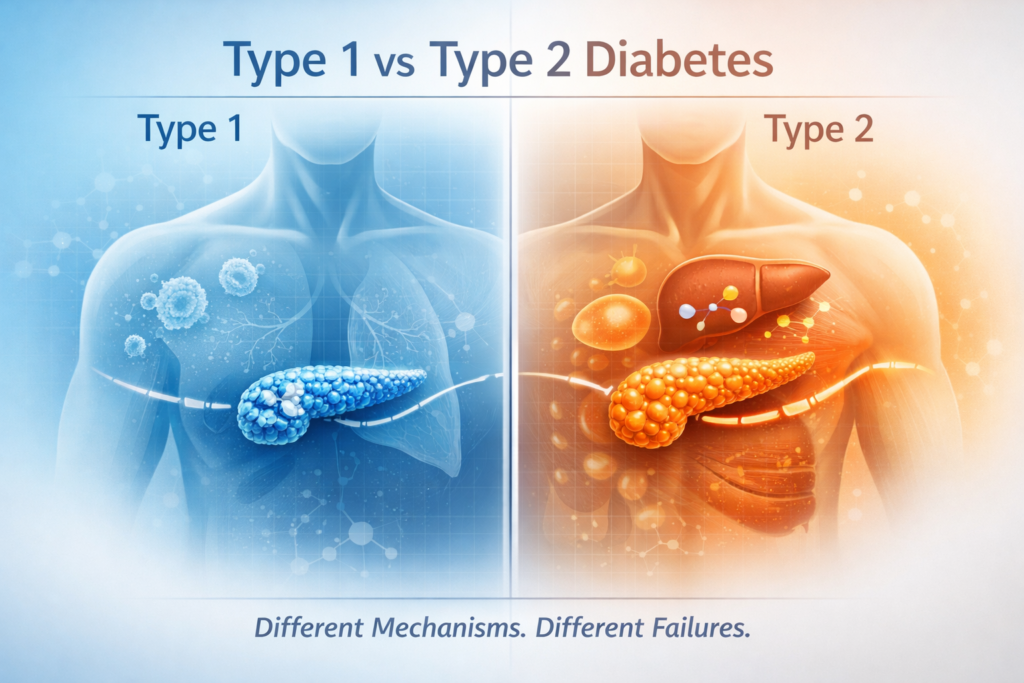

Difference Between Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes: 17 Critical Biological Differences Explained

Most discussions about diabetes begin with a contrast that sounds clear but explains very little. Type 1 diabetes is reduced to “no insulin” Type 2 diabetes is reduced to “insulin resistance”. These phrases are repeated so often that they are accepted as complete explanations, when in reality they describe only the final snapshot of two long, complex biological processes.

This kind of framing creates the illusion of understanding while hiding the mechanisms that actually matter. It compresses immune dysfunction, cellular stress, metabolic adaptation, and hormonal failure into two simplistic labels. The result is confusion among patients trying to understand their condition, clinicians trying to individualize treatment, and the public trying to make sense of risk, prevention, and outcomes.

Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes are not different expressions of the same disease, they are not points on a single spectrum. They are fundamentally distinct disorders that happen to intersect at one measurable outcome, elevated blood glucose. That shared endpoint has led to decades of conceptual overlap, despite the fact that the biological paths leading there are entirely different.

In Type 1 diabetes, the core problem originates in the immune system and ends in the destruction of insulin-producing cells. In Type 2 diabetes, the problem begins with metabolic overload and insulin resistance and evolves into progressive cellular exhaustion. These differences determine how quickly the disease appears, whether it can be modified, how it responds to treatment, and what long-term complications look like.

Understanding this distinction requires moving past glucose numbers and treatment algorithms and examining what is happening underneath, how beta cells function and fail, how tissues respond to insulin over time, how compensation masks disease for years, and how biological systems break down when adaptive capacity is exceeded.

Only by starting at this deeper level can the differences between Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes be understood clearly and only then can expectations, treatment decisions, and outcomes be aligned with biological reality.

Diabetes Is a Failure of Biological Regulation

Blood glucose regulation is often portrayed as a simple on or off process controlled by insulin. In reality, it is the output of a complex, tightly integrated regulatory network designed to keep circulating glucose within a narrow range across feeding, fasting, stress, illness, and physical activity.

At the center of this system are the pancreatic beta cells, which secrete insulin in precise amounts and timing, working in parallel are pancreatic alpha cells, which release glucagon to raise blood glucose when levels fall. The liver acts as both a storage organ and a glucose producer, switching between glycogen storage, glycogen breakdown, and gluconeogenesis depending on hormonal signals. Skeletal muscle and adipose tissue serve as major sites of glucose disposal, responding to insulin by increasing glucose uptake and utilization.

This system is further modulated by counter-regulatory hormones such as cortisol, epinephrine, and growth hormone, which protect against hypoglycemia during stress but also raise glucose levels when chronically elevated. Overlaying all of this is neural input from the central nervous system, integrating energy needs, stress responses, and circadian rhythms.

Diabetes develops when this regulatory network can no longer maintain equilibrium under ordinary physiological conditions. Importantly, the failure is not uniform across all components of the system.

In Type 1 diabetes, the system fails at its source, insulin production itself.

In Type 2 diabetes, insulin is produced often in excess but its effectiveness is progressively lost, and long-term compensation eventually collapses. This difference in the site of failure defines everything that follows.

1. Type 1 Diabetes: Autoimmune Destruction of Beta Cells

Core Pathophysiology

Type 1 diabetes is fundamentally an autoimmune disorder. The immune system mistakenly identifies pancreatic beta cells as foreign and mounts a sustained attack against them. Over time, this leads to progressive destruction of the cells responsible for insulin synthesis and secretion.

As beta-cell mass declines, endogenous insulin production falls below the threshold required to maintain metabolic stability. Eventually, insulin secretion becomes negligible or absent.

This is an absolute deficiency, unlike many hormonal systems, there is no redundant pathway capable of substituting for insulin’s metabolic functions without insulin, glucose cannot be appropriately taken up by muscle and adipose tissue, hepatic glucose output cannot be suppressed, and normal energy utilization breaks down.

The defining feature of Type 1 diabetes is not elevated glucose alone, but the loss of insulin as a biological signal.

Immune Mechanisms Driving Type 1 Diabetes

Under normal conditions, the immune system maintains tolerance to the body’s own tissues. In Type 1 diabetes, this tolerance collapses in a highly specific way that targets pancreatic beta cells.

Genetic susceptibility plays a central role, particularly variations in HLA class II genes that influence antigen presentation and immune regulation. These genes do not cause the disease on their own, but they create an immune environment in which tolerance is more fragile.

Environmental triggers appear necessary to initiate the autoimmune response. Viral infections are the leading candidates, as certain viral proteins resemble beta-cell antigens closely enough to confuse the immune system. This phenomenon, known as molecular mimicry, can activate autoreactive T cells that cross-react with beta-cell proteins.

Once activated, these immune cells drive a sustained inflammatory response within the pancreatic islets. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes, assisted by inflammatory cytokines, progressively damage and destroy beta cells.

Autoantibodies against beta-cell components such as GAD65, IA-2, ZnT8, and insulin itself are detectable during this process. These antibodies do not cause the destruction directly, but they serve as reliable markers of ongoing autoimmunity and often appear years before clinical symptoms develop.

Critically, insulin resistance is not the initiating factor in this disease. A person may have normal or even high insulin sensitivity and still develop Type 1 diabetes if immune-mediated beta-cell destruction occurs.

Progression and Clinical Onset of Type 1 Diabetes

The clinical onset of Type 1 diabetes often appears abrupt, but the underlying process is slow and progressive.

The disease typically begins with genetic and immunologic susceptibility, followed by the emergence of islet autoantibodies that signal immune activation. Over time, beta-cell mass steadily declines, but remaining cells can initially compensate, particularly at rest or under low metabolic demand.

As beta-cell reserve diminishes, the system begins to fail during periods of stress, illness, or increased glucose load. Glucose tolerance becomes impaired, post-prandial glucose rises, and insulin secretion becomes insufficient to maintain control.

Once a critical threshold of beta-cell loss is crossed, hyperglycemia becomes persistent and clinically apparent. At this stage, exogenous insulin becomes essential for survival.

This gradual progression explains several characteristic features of Type 1 diabetes, the seemingly sudden onset of symptoms, the temporary reduction in insulin requirements after diagnosis known as the honeymoon phase, and the frequent misclassification of adult patients as having Type 2 diabetes. In adults, this slower autoimmune process is often labeled latent autoimmune diabetes in adults, reflecting the same disease mechanism unfolding over a longer timeline.

What appears sudden at the bedside is the final stage of a failure that has been developing silently for years.

Metabolic Consequences of Absolute Insulin Deficiency

Insulin is not a single purpose hormone, it is the central coordinator of energy metabolism. When insulin is absent, multiple metabolic pathways fail simultaneously, creating a state of profound physiological instability.

In muscle and adipose tissue, glucose uptake becomes severely impaired because insulin-dependent glucose transporters are no longer activated. As a result, circulating glucose remains elevated despite cellular energy deprivation. At the same time, the liver loses insulin’s suppressive signal and continues producing glucose through glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, even when blood glucose levels are already dangerously high.

Insulin deficiency also removes restraint on fat breakdown. Lipolysis accelerates, releasing large quantities of free fatty acids into the circulation. These fatty acids are taken up by the liver and converted into ketone bodies as an alternative energy source. In the absence of insulin, ketone production becomes unchecked.

The combination of hyperglycemia, dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, and metabolic acidosis creates the clinical syndrome known as diabetic ketoacidosis. This condition is a defining and potentially fatal complication of Type 1 diabetes and reflects insulin absence rather than insulin resistance without insulin, the metabolic system defaults to a starvation state despite abundant circulating glucose.

2.Type 2 Diabetes: Failure of Metabolic Compensation

Core Pathophysiology

Type 2 diabetes follows a fundamentally different trajectory. It begins not with insulin deficiency, but with reduced tissue responsiveness to insulin’s actions. Muscle, liver, and adipose tissue gradually require higher and higher insulin concentrations to achieve the same metabolic effects.

In response, pancreatic beta cells increase insulin secretion in an effort to preserve normal glucose levels. For many years, this compensation is successful, blood glucose may remain entirely normal, and standard laboratory tests often fail to detect any abnormality.

This phase is commonly mistaken for metabolic health. In reality, it represents chronic physiological strain, elevated insulin levels are not benign, they signal that the system is operating under increasing pressure to maintain equilibrium.

Type 2 diabetes emerges not when insulin resistance first appears, but when the capacity to compensate for it begins to fail.

Origins of Insulin Resistance in Type 2 Diabetes

Insulin resistance does not arise from a single defect, it is the cumulative result of multiple interacting biological stresses.

Excess visceral adiposity plays a central role by releasing inflammatory mediators and free fatty acids directly into the portal circulation. These lipids accumulate within the liver and skeletal muscle, a process known as ectopic fat deposition, where fat is stored in tissues not designed to handle it.

This intracellular lipid accumulation disrupts insulin signaling pathways, impairing glucose uptake in muscle and reducing insulin’s ability to suppress hepatic glucose production. Chronic low-grade inflammation further interferes with insulin receptor function, while mitochondrial dysfunction reduces the cell’s capacity to utilize glucose efficiently.

Genetic susceptibility modifies all of these processes, influencing how easily insulin resistance develops and how effectively tissues adapt to metabolic stress. As insulin resistance worsens, beta cells respond by producing progressively larger amounts of insulin. Hyperinsulinemia becomes the price of maintaining normal glucose levels.

Progressive Beta-Cell Exhaustion in Type 2 Diabetes

Compensation is not limitless, sustained hyperinsulinemia places beta cells under continuous metabolic stress.

Repeated glucose spikes expose beta cells to glucotoxicity, while elevated free fatty acids induce lipotoxic damage. Oxidative stress accumulates, and the endoplasmic reticulum responsible for protein folding and insulin synthesis becomes dysfunctional. Over time, islet amyloid deposits form within the pancreas, further impairing cellular function.

One of the earliest detectable defects is the loss of first-phase insulin secretion, the rapid insulin response that normally occurs immediately after food intake, without this response, postprandial glucose levels rise disproportionately.

By the time Type 2 diabetes is clinically diagnosed, many individuals have already lost 40 to 60 percent of functional beta-cell capacity. Insulin levels may still be measurable, or even elevated, but they are no longer adequate for the degree of insulin resistance present.

This represents relative insulin deficiency, not absolute absence. The distinction is critical for understanding both treatment and prognosis.

Beta-Cell Failure as the Central Divider

The most important distinction between Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes lies not in glucose levels, age of onset, or body size, but in the nature of beta-cell failure.

In Type 1 diabetes, beta cells are destroyed by immune-mediated mechanisms. Once lost, they cannot be regenerated with current medical technology.

In Type 2 diabetes, beta cells are damaged by chronic metabolic stress. Early in the disease course, this damage may be partially reversible if the underlying stressors are reduced. Later, irreversible loss occurs.

This difference determines how rapidly the disease progresses, whether remission is possible, how treatments work, and what long-term outcomes can be expected.

Understanding diabetes without understanding beta-cell biology guarantees incomplete management.

Genetics: Susceptibility Versus Expression

Type 1 Diabetes Genetics

Type 1 diabetes has strong genetic associations within the HLA region, which governs immune recognition and tolerance. These genes influence how the immune system responds to environmental exposures, particularly viral antigens.

Genetics create susceptibility, not certainty. Many individuals with high-risk genotypes never develop Type 1 diabetes, underscoring the requirement for environmental triggers and immune activation.

Type 2 Diabetes Genetics

Type 2 diabetes is polygenic, involving hundreds of genetic variants that affect insulin secretion, fat distribution, appetite regulation, energy expenditure, and cellular metabolism.

Unlike Type 1 diabetes, genetic risk in Type 2 diabetes is highly modifiable. Environmental exposure, dietary patterns, physical activity, sleep, stress, and early-life metabolic programming determines whether genetic risk is expressed clinically. Genes influence vulnerability, environment determines outcome.

Age of Onset Is a Poor Diagnostic Tool

Historically, diabetes was divided into “juvenile” and “adult-onset” forms. This distinction is biologically meaningless.

Type 1 diabetes can develop at any age, including late adulthood.

Type 2 diabetes is increasingly diagnosed in adolescents and even children.

Relying on age to infer mechanism leads to misdiagnosis, delayed insulin initiation in Type 1 diabetes, and inappropriate treatment strategies in both conditions. Disease biology does not respect age categories.

Body Weight Is Not Causation

Body weight is frequently overemphasized in discussions of diabetes, particularly Type 2 diabetes. While excess weight is associated with increased risk, it does not define the disease.

Lean individuals can exhibit severe insulin resistance and develop Type 2 diabetes. Conversely, many individuals with obesity never develop diabetes at all. What matters more than total body weight is fat distribution, particularly visceral and ectopic fat accumulation.

Similarly, people with Type 1 diabetes may gain weight after insulin therapy due to restoration of normal anabolic signaling and improved metabolic efficiency.

Weight modifies risk, it does not determine mechanism, cause, or diagnosis. Confusing association with causation obscures the true biology of diabetes and misdirects both prevention and treatment efforts.

Treatment Implications of Mechanism-Based Thinking

Treating Type 1 Diabetes

Insulin replacement is mandatory and lifelong, management focuses on physiologic insulin delivery, glucose monitoring, and prevention of hypoglycemia and ketoacidosis. Lifestyle measures support health but cannot replace insulin.

Treating Type 2 Diabetes

Treatment targets multiple defects: insulin resistance, hepatic glucose output, beta-cell preservation, and metabolic overload. Insulin may be necessary but should not substitute for addressing underlying resistance.

Complications: Shared Outcomes, Different Drivers

Both types can cause retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, and cardiovascular disease. In Type 1 diabetes, complication risk correlates primarily with disease duration and cumulative glycemic exposure.

In Type 2 diabetes, complications arise from combined effects of hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction.

Reversibility and Remission

Type 1 diabetes cannot currently be reversed due to permanent beta-cell loss.

Type 2 diabetes may enter remission if early intervention reduces metabolic stress and restores insulin sensitivity. Remission requires sustained control and is not a cure.

The Cost of Oversimplification

Reducing diabetes to lifestyle choices or sugar intake promotes stigma, delays care, and results in inappropriate treatment.

Type 1 diabetes is not preventable by behavior.

Type 2 diabetes is not simply a failure of discipline. Both are biological diseases governed by physiology.

Final Perspective

Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes share a name, not a mechanism. One arises from immune destruction of insulin-producing cells.

The other develops from insulin resistance followed by cellular exhaustion.

They converge at elevated blood glucose but arrive there through entirely different biological paths. Blood sugar is the visible signal, the disease process lies beneath it. Treating numbers without understanding mechanism guarantees incomplete control.

🩺 Talk to a Health Expert Today

Personalized advice matters. Connect with licensed doctors at MuseCare Consult to review your symptoms, labs, or medications in a private, convenient session.

👉 Schedule Your ConsultMust Read:

- Diabetes Mellitus: 10 Essential Insights on Causes, Types, Symptoms, Complications, and Modern Management

- How Blood Sugar Is Regulated in the Body: 10 Key Mechanisms Explained

- 10 Proven Benefits of Nutritional Counseling for Diabetes Management

- 12 Powerful Early Signs of Insulin Resistance You Should Watch and How to Fix Them

- 10 Proven Tips on How to Interpret Hemoglobin A1c Levels Accurately

- 7 Surprising Reasons Why Your Blood Sugar Spikes After Eating Low-Carb Meals

Dr. Ijasusi Bamidele, MBBS (Binzhou Medical University, China), is a medical doctor with 5 years of clinical experience and founder of MyMedicalMuse.com, a subsidiary of Delimann Limited. As a health content writer for audiences in the USA, Canada, and Europe, Dr. Ijasusi helps readers understand complex health conditions, recognize why they have certain symptoms, and apply practical lifestyle modifications to improve well-being