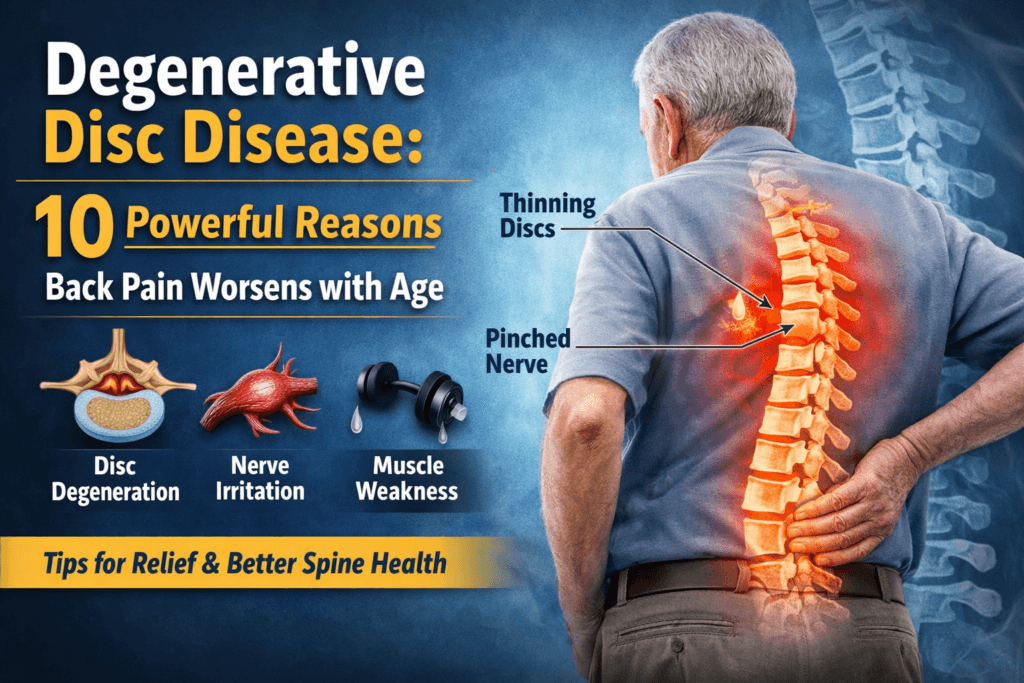

Degenerative Disc Disease: 10 Powerful Reasons Back Pain Worsens With Age

Back pain is one of the most common reasons people seek medical care worldwide, and its likelihood increases steadily with age. What often begins as occasional stiffness or discomfort can gradually evolve into persistent pain that interferes with work, sleep, and daily life. Among the many conditions blamed for age-related back pain. Degenerative disc disease is one of the most frequently misunderstood and most often feared.

Despite its name, degenerative disc disease is not an infection, not cancer, and not a condition that automatically leads to disability. It is a medical term used to describe the natural, age-related wear and structural changes that occur in the spinal discs over time. These changes are a normal part of human aging, much like graying hair or reduced skin elasticity. The problem arises when disc degeneration begins to disrupt spinal stability, irritate nearby nerves, or trigger chronic inflammation turning normal aging into persistent pain.

As spinal discs lose hydration, flexibility, and shock-absorbing capacity, the spine becomes less tolerant of everyday stresses such as sitting, bending, lifting, or prolonged standing. For many people, this explains why back pain tends to worsen with age, why flare-ups become more frequent, and why recovery from minor strain takes longer than it did in younger years. Importantly, disc degeneration alone does not guarantee pain but when combined with mechanical overload, joint arthritis, muscle weakness, or nerve compression, symptoms can escalate.

Understanding why degenerative disc disease develops, how aging amplifies its effects, and what modern medicine can realistically offer is essential for making informed decisions. Misconceptions often lead to unnecessary fear, overtreatment, or inactivity each of which can worsen outcomes rather than improve them.

This article explains the biological and mechanical science behind disc degeneration, clarifies why back pain often intensifies with age, and outlines evidence-based approaches to managing symptoms, preserving mobility, and maintaining long-term spine health. The goal is not false reassurance but clarity, accuracy, and practical understanding.

Understanding the Structure of Spinal Discs

The human spine is a complex mechanical structure designed to balance strength, stability, and flexibility. It is composed of 33 vertebrae, most of which are separated by intervertebral discs specialized structures that function as shock absorbers and motion regulators. These discs allow the spine to bend, twist, and bear weight while protecting the vertebrae from direct impact during movement.

Without healthy discs, ordinary activities such as walking, sitting, or lifting would transmit excessive force directly to bone and joints, leading to pain and injury.

Each intervertebral disc consists of two distinct but interdependent components:

- Nucleus pulposus: a gel-like, water-rich core that absorbs compressive forces and distributes pressure evenly across the disc

- Annulus fibrosus: a tough, fibrous outer ring composed primarily of collagen layers that contain the nucleus and provide structural integrity

In youth and early adulthood, spinal discs are highly hydrated, elastic, and resilient. Their high water content allows them to deform under load and then return to their original shape once the load is removed. This property enables efficient shock absorption and smooth spinal motion, even under significant mechanical stress.

With aging, however, these biomechanical properties gradually change and those changes form the biological foundation of degenerative disc disease.

What Is Degenerative Disc Disease?

Degenerative disc disease is a medical term used to describe the progressive structural and functional deterioration of intervertebral discs over time. Despite the word disease, it does not imply infection, inflammation alone, or an abnormal process. Instead, it reflects the cumulative effects of aging, mechanical loading, and biological change on disc tissue.

Key features of degenerative disc disease include:

- Loss of disc hydration, reducing shock-absorbing capacity

- Decreased disc height, narrowing the space between vertebrae

- Weakening or tearing of the annulus fibrosus, increasing vulnerability to bulging or herniation

- Altered load distribution, shifting stress to facet joints and ligaments

- Secondary degenerative changes in surrounding spinal structures

Crucially, disc degeneration is extremely common and does not automatically cause pain. Imaging studies consistently show signs of disc degeneration in more than 40% of adults under 40 years old and in over 90% of people above 60, many of whom have no symptoms at all.

Pain develops when disc degeneration leads to mechanical instability, inflammatory signaling, or irritation of nearby nerves. In other words, degeneration is often the background condition, while pain emerges from its downstream effects.

Why Disc Degeneration Is Closely Linked to Aging

Aging affects spinal discs through multiple overlapping mechanisms. These processes unfold gradually over decades, which explains why symptoms often appear or worsen later in life rather than suddenly.

1. Progressive Loss of Disc Hydration

Water content is central to disc function. In early adulthood, intervertebral discs are composed of approximately 70-90% water, largely retained by proteoglycans within the nucleus pulposus.

With age:

- Proteoglycan concentration declines

- The disc’s ability to bind and retain water diminishes

- Disc tissue becomes stiffer and less compliant

As hydration decreases, discs lose their capacity to absorb compressive forces efficiently. Instead of distributing load evenly, mechanical stress becomes concentrated in specific areas, increasing susceptibility to micro-injury during everyday activities such as bending, lifting, or prolonged sitting.

2. Reduced Nutrient Supply to Discs

Unlike muscles or bones, intervertebral discs do not have a direct blood supply. They rely on passive diffusion of oxygen, glucose, and nutrients through the vertebral endplates.

As aging progresses:

- Endplates become thicker and more calcified

- Nutrient diffusion becomes less efficient

- Waste product removal slows

This compromised nutrient exchange leads to disc cell death, reduced metabolic activity, and impaired repair mechanisms. Even minor structural damage that would heal in younger tissue may persist or worsen in aging discs.

3. Cumulative Mechanical Stress Over Time

The spine is subjected to mechanical load continuously during standing, sitting, walking, twisting, and lifting. Over decades, this cumulative stress produces gradual wear that cannot be avoided entirely.

Long-term mechanical loading contributes to:

- Micro-tears in the annulus fibrosus

- Progressive disc height reduction

- Subtle changes in spinal alignment and motion patterns

Certain factors accelerate this process, including poor posture, obesity, repetitive heavy labor, prolonged sitting, and sedentary lifestyles. Rather than a single injury, degenerative disc disease reflects the accumulated impact of millions of small stresses over time.

4. Age-Related Changes in Collagen and Disc Matrix

The structural integrity of discs depends heavily on collagen organization and elasticity with aging:

- Collagen fibers become stiffer and less orderly

- Elastic recoil decreases

- Disc tissue becomes more brittle and less tolerant of deformation

These changes reduce the disc’s ability to withstand sudden or uneven forces, increasing the likelihood of disc bulging, herniation, or collapse, particularly during unexpected strain or poor movement mechanics.

5. Decline in the Body’s Repair Capacity

Younger bodies respond to tissue stress with efficient repair and balanced inflammation. Aging disrupts this equilibrium.

Over time:

- Low-grade chronic inflammation becomes more prevalent

- Cellular repair processes slow

- Degenerative changes accumulate faster than healing

As a result, a minor back strain that would resolve quickly in youth may linger, recur, or progressively worsen later in life. This decline in repair capacity explains why disc degeneration often becomes clinically relevant with advancing age, even if structural changes began decades earlier.

Why Back Pain Often Worsens With Age

Disc degeneration alone does not automatically cause pain. Many people have significant degenerative changes on imaging yet remain largely symptom-free. Back pain tends to worsen with age when disc degeneration triggers secondary structural, mechanical, and neurological effects that overwhelm the spine’s ability to compensate.

As these changes accumulate, everyday movements place increasing stress on pain-sensitive tissues, making symptoms more frequent, persistent, and harder to ignore.

1. Loss of Disc Height and Spinal Instability

As intervertebral discs lose hydration and structural integrity, they gradually lose height. This reduction in disc height alters normal spinal mechanics in several ways:

- Vertebrae move closer together, narrowing joint spaces

- Facet joints are forced to bear a greater share of mechanical load

- Abnormal motion patterns develop between spinal segments

This altered movement creates segmental instability, which irritates ligaments, joint capsules, and surrounding soft tissues. Pain often worsens during movement, prolonged sitting, or standing because unstable segments are repeatedly stressed under load.

2. Increased Stress on Facet Joints

Facet joints play a critical role in guiding and limiting spinal motion. When disc height is preserved, these joints share load evenly with the discs. As discs degenerate and collapse, stress is redirected toward the facet joints.

Over time, this leads to facet joint osteoarthritis, characterized by:

- Localized back or neck pain

- Morning stiffness or stiffness after inactivity

- Pain worsened by spinal extension, twisting, or rotation

Facet arthritis frequently coexists with degenerative disc disease in older adults and is a common, often overlooked source of chronic spinal pain.

3. Nerve Compression and Inflammation

Degenerating discs may bulge, protrude, or herniate, reducing space within the spinal canal or neural foramina, the passages through which spinal nerves exit.

This narrowing can cause:

- Sciatica, resulting from lumbar nerve root compression

- Cervical radiculopathy, causing neck pain radiating into the arms

- Sensory changes such as numbness or tingling

- Muscle weakness in severe or prolonged cases

Age-related changes further compound this problem. Thickening of spinal ligaments, development of bone spurs, and facet joint enlargement all contribute to progressive nerve compression and inflammation.

4. Reduced Shock Absorption

Healthy discs protect the spine by absorbing and distributing mechanical forces. As discs degenerate, this shock-absorbing capacity diminishes.

Instead of being cushioned by flexible discs, impact forces are transmitted directly to:

- Vertebral bodies

- Facet joints

- Supporting ligaments and muscles

As a result, ordinary activities such as walking on hard surfaces, sitting for long periods, or lifting light objects can provoke disproportionate pain.

5. Muscle Weakness and Physical Deconditioning

Aging is associated with sarcopenia, the gradual loss of muscle mass and strength. When core and spinal stabilizing muscles weaken:

- Spinal support decreases

- Mechanical load on discs and joints increases

- Movement becomes less efficient and more stressful

Pain often leads people to reduce activity, which accelerates muscle weakness. This creates a self-reinforcing cycle: pain causes inactivity, inactivity worsens weakness, and weakness increases spinal stress leading to more pain.

Common Symptoms of Degenerative Disc Disease

Symptoms vary widely depending on the affected spinal level, severity of degeneration, and individual pain sensitivity. Common presentations include:

- Chronic low back or neck pain

- Pain worsened by sitting, bending, lifting, or prolonged postures

- Symptom relief with walking or frequent position changes

- Radiating pain into the arms or legs

- Intermittent flare-ups rather than constant pain

- Stiffness after inactivity or upon waking

Importantly, symptom severity does not always match imaging findings. Some individuals with advanced disc degeneration experience minimal discomfort, while others with relatively mild structural changes report significant pain. This mismatch highlights the importance of clinical context over imaging alone.

Risk Factors That Accelerate Disc Degeneration

While aging itself cannot be avoided, several factors increase the rate and severity of disc degeneration:

- Smoking, which reduces disc oxygenation and nutrient delivery

- Obesity, which increases mechanical load on the spine

- Sedentary lifestyle and poor muscle conditioning

- Repetitive heavy lifting or occupational strain

- Poor posture and ergonomics

- Genetic predisposition affecting disc composition

- Diabetes and other metabolic conditions

Addressing modifiable risk factors can meaningfully slow progression and reduce symptom burden even later in life.

How Degenerative Disc Disease Is Diagnosed

Accurate diagnosis relies on clinical evaluation supported by imaging, not imaging in isolation.

Clinical Assessment

- Detailed pain history and symptom patterns

- Identification of aggravating and relieving factors

- Neurological examination for strength, sensation, and reflexes

- Assessment of functional limitations and movement patterns

Imaging Studies

- X-ray to evaluate disc height loss and spinal alignment

- MRI to assess disc hydration, bulges, herniation, and nerve compression

- CT scan to visualize bony changes when surgical planning is considered

Imaging findings must always be interpreted in the context of symptoms. Treating MRI results without clinical correlation frequently leads to unnecessary interventions and poor outcomes.

Treatment: What Actually Works

Degenerative disc disease is manageable, not curable. Structural disc changes cannot be reversed, but pain, function, and quality of life can often be improved substantially. The primary goals of treatment are symptom control, preservation of mobility, prevention of disability, and long-term functional independence.

For most people, effective management does not involve surgery. Treatment follows a stepwise approach, beginning with conservative strategies and escalating only when necessary.

1. Conservative (First-Line) Management

The majority of patients with degenerative disc disease experience meaningful improvement with non-surgical care. These approaches target mechanical stress, inflammation, muscle support, and movement patterns rather than disc structure itself.

Physical Therapy

Targeted physical therapy is the cornerstone of treatment and has the strongest evidence for long-term benefit.

Key components include:

- Core strengthening to stabilize the spine and reduce abnormal segmental motion

- Flexibility training to restore balanced movement and reduce compensatory strain

- Postural correction to minimize chronic mechanical overload

Effective therapy focuses on gradual, progressive loading rather than passive treatments alone.

Lifestyle Modifications

Everyday habits significantly influence symptom progression.

Important modifications include:

- Weight management to reduce axial load on spinal structures

- Smoking cessation, which improves disc oxygenation and tissue healing

- Ergonomic adjustments at work and home to reduce repetitive strain

These changes do not reverse degeneration but can markedly reduce symptom severity.

Medications

Medications are used to control symptoms, not as a standalone solution.

Common options include:

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to reduce inflammation and pain

- Short-term muscle relaxants for acute muscle spasm

Long-term opioid use is not recommended due to limited benefit and significant risk. Medications should support activity and rehabilitation not replace them.

Activity Modification

Contrary to outdated advice, prolonged rest is harmful.

Recommended strategies include:

- Remaining physically active within tolerance

- Avoiding extended bed rest

- Limiting prolonged sitting and static postures

- Encouraging frequent position changes

Movement promotes circulation, muscle engagement, and pain modulation.

2. Interventional Treatments

When conservative treatment fails to provide adequate relief, minimally invasive interventions may be considered to reduce pain and facilitate rehabilitation.

These options include:

- Epidural steroid injections to reduce nerve root inflammation

- Facet joint injections to address facet-mediated pain

- Selective nerve blocks for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes

These interventions can provide temporary symptom relief, allowing patients to participate more effectively in physical therapy. However, they do not repair discs or stop degeneration and should be used selectively rather than repeatedly.

3. Surgical Options

Surgery is reserved for a small subset of patients and is not a treatment for aging itself.

Surgical intervention may be appropriate when:

- Comprehensive conservative treatment fails over an adequate time frame

- Progressive neurological deficits develop (e.g., weakness, bowel or bladder dysfunction)

- Pain severely limits daily function despite optimized non-surgical care

Common surgical procedures include:

- Discectomy, removing disc material compressing a nerve

- Spinal fusion, stabilizing painful motion segments

- Artificial disc replacement, suitable for carefully selected patients

Surgery addresses specific mechanical problems but does not halt the aging process or prevent degeneration at adjacent levels.

Can Degenerative Disc Disease Be Prevented?

Disc degeneration cannot be completely prevented, but its rate of progression and symptom impact can be reduced.

Evidence-based preventive strategies include:

- Regular low-impact aerobic exercise

- Consistent core strengthening

- Maintaining a healthy body weight

- Avoiding tobacco use

- Practicing proper lifting and movement mechanics

- Managing metabolic conditions such as diabetes

Importantly, aging does not automatically lead to disabling back pain. Many individuals maintain functional, active lives despite radiographic degeneration.

The Psychological Component of Chronic Back Pain

Chronic back pain is not purely a structural problem. Over time, persistent pain alters how the nervous system processes signals.

With aging and chronic pain:

- Pain thresholds may decrease

- Central sensitization can amplify pain perception

- Anxiety, fear of movement, and catastrophizing become more common

These psychological factors can intensify symptoms even when structural damage is stable. Addressing stress, mental health, and pain-coping strategies, through education, cognitive-behavioral approaches, and graded activity is essential for long-term success.

The Bottom Line

Degenerative disc disease is a normal consequence of aging, not a sign of weakness or failure. Back pain worsens with age because spinal discs lose hydration, elasticity, and repair capacity, leading to instability, joint overload, and nerve irritation.

However, degeneration does not equal disability, with appropriate lifestyle choices, evidence-based treatment, and realistic expectations, most people with degenerative disc disease can remain active, functional, and independent well into older age.

Back pain is not simply something to put up with,

understanding its biological roots is the first step toward managing it intelligently and effectively.

👩⚕️ Need Personalized Health Advice?

Get expert guidance tailored to your unique health concerns through MuseCare Consult. Our licensed doctors are here to help you understand your symptoms, medications, and lab results—confidentially and affordably.

👉 Book a MuseCare Consult NowMust Read:

- Essential Guide to Lower Back, Joint, and Bone Pain: Causes, Diagnosis, and Effective Treatments

- Lower Back Pain Radiates to the Leg: 7 Key Causes, Diagnosis & Treatments

- Osteoarthritis vs Rheumatoid Arthritis: 7 Key Pain Patterns You Must Know

- MRI vs X-Ray vs CT Scan for Pain Diagnosis: 5 ways to Choose the Right Imaging

- 7 Back or Joint Pain Red Flags You Shouldn’t Ignore

- Herniated Disc vs Bulging Disc: 13 Key Differences & Lower Back Pain Explained

Dr. Ijasusi Bamidele, MBBS (Binzhou Medical University, China), is a medical doctor with 5 years of clinical experience and founder of MyMedicalMuse.com, a subsidiary of Delimann Limited. As a health content writer for audiences in the USA, Canada, and Europe, Dr. Ijasusi helps readers understand complex health conditions, recognize why they have certain symptoms, and apply practical lifestyle modifications to improve well-being