Herniated Disc vs Bulging Disc: 13 Key Differences & Lower Back Pain Explained

Lower back pain doesn’t appear out of nowhere and it’s rarely as simple as a bad back. In many cases, the real issue lies deeper, inside the spine itself, where intervertebral discs quietly absorb stress every day. When these discs begin to fail, two diagnoses come up again and again: bulging discs and herniated discs. They’re often mentioned in the same breath, frequently confused, and sometimes treated as interchangeable, yet they are not the same problem, and they don’t affect the body in the same way.

This guide cuts through the confusion, You’ll learn what actually separates a bulging disc from a herniated disc, why one is more likely to cause serious lower back pain, how symptoms differ, and what medical evidence says about diagnosis, treatment, and long-term prevention. If you’ve ever been told you have a disc issue and left wondering what that really means for your pain or your future, this breakdown gives you clear, clinically grounded answers.

Understanding the Spine and Intervertebral Discs

To understand why disc problems cause lower back pain, you first need a clear picture of how the spine is built and how it functions under daily stress. The human spine is a complex, weight-bearing structure made up of 33 vertebrae, stacked vertically to protect the spinal cord while allowing movement and flexibility. These vertebrae are grouped into distinct regions: the cervical spine (neck), thoracic spine (mid-back), lumbar spine (lower back), sacrum, and coccyx.

The lumbar spine is especially important when discussing back pain. It carries the majority of the body’s weight and absorbs forces generated by walking, lifting, bending, and twisting. Between each vertebra lies an intervertebral disc, a specialized structure designed to act as both a shock absorber and a motion facilitator, without these discs, even simple movements would be painful and mechanically inefficient.

Anatomy of an Intervertebral Disc

Each intervertebral disc is made up of two distinct components that work together to manage spinal load:

- Nucleus Pulposus

This is the soft, gel-like center of the disc. Its primary role is to distribute pressure evenly across the disc when the spine is under stress, such as during standing, lifting, or sudden movements. In healthy discs, the nucleus contains a high water content, which allows it to compress and rebound effectively. - Annulus Fibrosus

Surrounding the nucleus is the annulus fibrosus, a tough, layered ring of fibrous tissue. This outer structure provides strength and stability, keeping the nucleus contained while allowing controlled movement between vertebrae. The annulus is designed to withstand significant forces, but it can weaken over time.

Healthy discs maintain spinal alignment, absorb shock, and allow smooth motion. However, aging, mechanical stress, or injury can compromise disc integrity. When this happens, the disc may begin to deform or fail, leading to conditions such as disc bulging or disc herniation, two problems that are related but not identical.

Bulging Disc: Definition and Causes

A bulging disc occurs when the disc extends beyond its normal anatomical boundary but without tearing the outer annulus fibrosus. In simple terms, the disc flattens and pushes outward, often evenly around its circumference. A common analogy is a jelly-filled donut being gently squeezed, the donut bulges outward, but the jelly stays contained.

Bulging discs usually develop gradually, making them more strongly associated with long-term spinal wear rather than sudden injury. They are extremely common, particularly in adults over the age of 40, and are often considered part of the natural aging process of the spine.

Causes of Bulging Discs

Several factors contribute to the development of bulging discs:

- Age-Related Degeneration

As discs age, they lose water content and elasticity. This dehydration reduces their ability to maintain shape and resist pressure, making outward bulging more likely. - Repetitive Mechanical Stress

Jobs or activities involving frequent bending, lifting, or twisting especially with poor technique, place continuous strain on spinal discs. - Poor Posture

Prolonged sitting, slouching, or forward-head posture increases pressure on lumbar discs, accelerating degeneration over time. - Obesity and Excess Body Weight

Additional body weight increases axial load on the lower spine, forcing discs to absorb more stress than they are designed to handle. - Genetic Predisposition

Some individuals inherit weaker connective tissue or a tendency toward early disc degeneration, increasing their risk even with minimal mechanical stress.

Symptoms of a Bulging Disc

One of the most important facts about bulging discs is that most of them do not cause pain. Many people live for years with disc bulges and never experience symptoms. These bulges are often discovered incidentally during imaging performed for unrelated reasons.

When symptoms do occur, they tend to be milder and less specific than those caused by a herniated disc. Common symptoms include:

- Mild to moderate lower back pain

- Dull aching or stiffness, especially after prolonged sitting or inactivity

- Reduced spinal flexibility or tightness in the lower back

- Numbness or tingling in the legs if the bulge presses on a nearby nerve root

Pain from a bulging disc often fluctuates, worsening with prolonged sitting, bending, or poor posture, and improving with movement or position changes.

Importantly, disc bulging alone does not equal pain. Large imaging studies have shown that up to 70-80% of adults have bulging discs visible on MRI despite having no back pain at all. This is why symptoms not imaging findings alone, should guide diagnosis and treatment decisions.

In many cases, a bulging disc becomes clinically significant only if it progresses, becomes inflamed, or contributes to nerve compression. Understanding this distinction is critical before assuming that a disc bulge is the primary cause of lower back pain.

Herniated Disc: Definition and Causes

A herniated disc, sometimes called a slipped or ruptured disc, occurs when the inner core of the disc, the nucleus pulposus, breaks through a tear or weak point in the annulus fibrosus. Unlike a bulging disc, where the outer layer remains intact, a herniated disc involves a structural failure of the disc wall. A useful analogy is a jelly-filled donut that has been squeezed until the jelly actually spills out.

This distinction matters because the material that escapes from the disc is biologically active. When it comes into contact with spinal nerves, it can trigger both mechanical compression and chemical inflammation, making herniated discs far more likely to cause pain, numbness, weakness, or neurological symptoms than bulging discs.

Herniated discs most commonly affect the lumbar spine, particularly the L4-L5 and L5-S1 levels, where spinal load and motion are greatest.

Causes of Herniated Discs

Herniated discs often arise from the same long-term degenerative processes that cause disc bulging, but they typically involve an additional acute stressor that pushes the disc past its breaking point.

Common causes include:

- Sudden Trauma or Improper Lifting

Lifting a heavy object with poor technique, especially twisting while lifting or experiencing a fall can cause a sudden spike in disc pressure, leading to annular tears and herniation. - Age-Related Disc Degeneration

As discs lose hydration and elasticity with age, the annulus fibrosus becomes more brittle and prone to tearing. This makes herniation more likely even with relatively minor stress. - Repetitive Motion and Overuse

Occupations or activities involving repeated bending, twisting, or vibration (such as long-distance driving) progressively weaken disc structures. - Genetic Predisposition

Some individuals inherit weaker connective tissue or disc composition that increases susceptibility to early herniation. - Lifestyle Factors

Smoking reduces blood flow and oxygen delivery to spinal tissues, accelerating disc degeneration. A sedentary lifestyle weakens core muscles that normally help stabilize and protect the spine.

In many cases, a herniated disc represents the end stage of a degenerative process that may have started years earlier with disc bulging or disc dehydration.

Symptoms of a Herniated Disc

Herniated discs are far more likely than bulging discs to produce clear, clinically significant symptoms, especially when nerve roots are involved.

Common symptoms include:

- Sharp or severe lower back pain, often sudden in onset

- Radiating leg pain (sciatica), typically following the path of the sciatic nerve into the buttock, thigh, calf, or foot.

- Numbness, tingling, or pins-and-needles sensations in the legs or feet

- Muscle weakness, which may affect walking, standing, or foot control

- Pain worsened by coughing, sneezing, or straining, due to increased spinal pressure

- Muscle spasms and reduced range of motion, caused by protective muscle guarding

The severity and pattern of symptoms depend on the exact location of the herniation and which nerve roots are affected. A small herniation pressing directly on a nerve can cause more pain than a larger herniation that does not contact neural tissue.

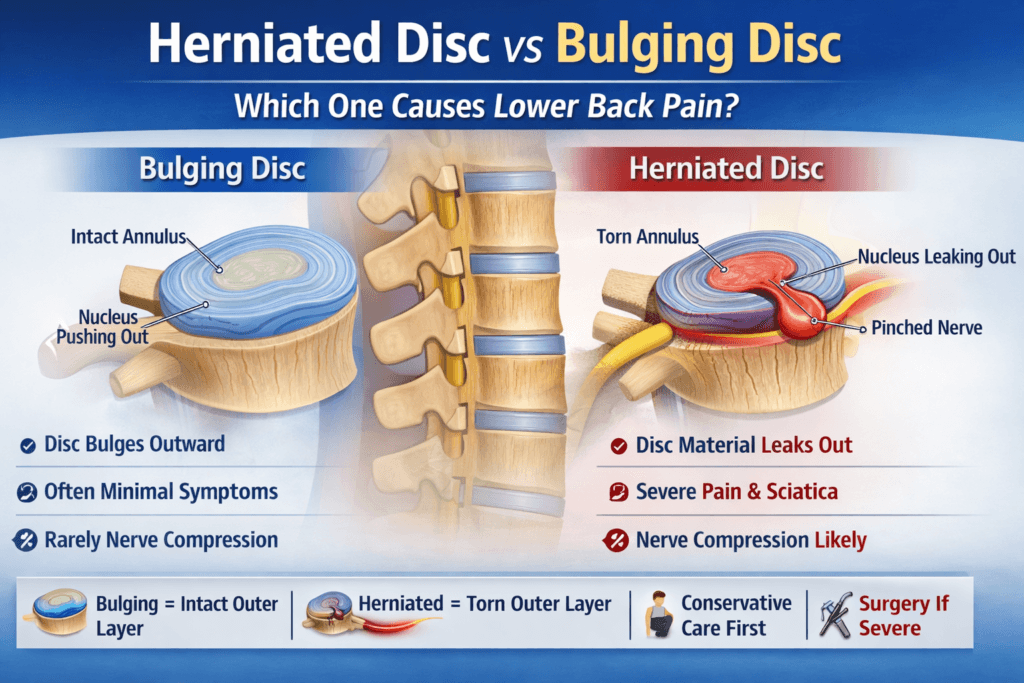

Key Differences Between Bulging and Herniated Discs

Feature | Bulging Disc | Herniated Disc |

Disc Integrity | Outer layer intact | Outer layer torn, nucleus escapes |

Pain Likelihood | Often asymptomatic | Frequently painful |

Onset | Gradual, degenerative | Often sudden or acute |

Nerve Compression | Less common | Much more common |

Inflammatory Response | Minimal | Significant |

Treatment Complexity | Usually conservative | May require injections or surgery if severe |

These distinctions are clinically critical. A diagnosis of disc problem without specifying bulging versus herniation can be misleading and may result in inappropriate treatment expectations.

How Discs Cause Lower Back Pain

Lower back pain related to disc pathology arises primarily through two mechanisms: nerve compression and inflammation. The lumbar spine particularly the L4-L5 and L5-S1 segments is especially vulnerable because it bears the highest mechanical load and allows significant movement.

- Bulging discs may cause pain by subtly narrowing spinal canals or nerve exit pathways, leading to intermittent nerve irritation. Symptoms are often mild, positional, and inconsistent.

- Herniated discs are more likely to cause pain because the displaced disc material can directly compress nerve roots, producing sharp, radiating pain and neurological deficits.

- Chemical inflammation plays a major role. The nucleus pulposus contains inflammatory substances that are normally sealed inside the disc. When released, these chemicals sensitize nearby nerves and tissues, causing pain even in the absence of significant mechanical compression.

This explains why some patients experience severe pain despite relatively small herniations on imaging, while others with larger abnormalities remain relatively comfortable.

Understanding these mechanisms helps clarify why herniated discs are generally more symptomatic than bulging discs, and why imaging findings must always be interpreted alongside clinical symptoms not in isolation.

Diagnosis: Bulging Disc vs Herniated Disc

Accurate diagnosis is critical because imaging findings alone do not always explain pain. Many people have disc abnormalities without symptoms, while others experience significant pain with minimal visible changes. For this reason, clinicians rely on a combination of clinical evaluation and targeted testing, not a single scan.

Medical History and Physical Examination

The diagnostic process begins with a detailed history and physical exam. Physicians assess:

- The pattern of pain (localized vs radiating)

- Pain triggers such as sitting, bending, coughing, or lifting

- Presence of numbness, tingling, or weakness

- Reflex changes and muscle strength

- Sensory deficits along specific nerve distributions

This step helps distinguish disc-related pain from muscle strain, facet joint problems, or spinal stenosis.

Imaging Studies

Imaging confirms the diagnosis and clarifies the type of disc involvement:

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging)

The gold standard for evaluating spinal discs and nerve structures. MRI can clearly differentiate between a bulging disc and a herniated disc and identify nerve compression, inflammation, or spinal canal narrowing. - CT Scan

Useful when MRI is contraindicated (such as in patients with certain implanted devices). CT scans provide good detail of bony structures and can identify large disc herniations. - X-ray

While X-rays do not show discs directly, they help rule out fractures, instability, or severe degenerative changes that may contribute to symptoms.

Nerve Function Tests

- Electromyography (EMG) and Nerve Conduction Studies

These tests assess how well nerves and muscles are functioning. They are particularly helpful when symptoms persist or when the extent of nerve damage is unclear.

A correct diagnosis not only guides treatment decisions but also helps set realistic expectations for recovery and long-term outcomes.

Treatment Options

Most disc-related back pain improves without surgery. The treatment approach depends on symptom severity, neurological findings, and response to initial therapy.

1. Conservative (Non-Surgical) Treatment

This is the first-line approach for both bulging and herniated discs.

- Physical Therapy

Focuses on core strengthening, spinal stabilization, flexibility, and posture correction to reduce disc pressure and improve movement patterns. - Medications

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, or short-term muscle relaxants help control pain and inflammation. - Lifestyle Modifications

Weight management, ergonomic adjustments at work, smoking cessation, and activity pacing significantly reduce disc stress and improve healing. - Heat and Ice Therapy

Ice reduces acute inflammation, while heat helps relax muscles and improve blood flow during recovery. - Activity Modification

Temporary avoidance of heavy lifting, repetitive bending, or twisting allows inflamed tissues to settle without complete bed rest, which can worsen outcomes.

Most patients experience significant improvement within 6-8 weeks using these measures alone.

2. Minimally Invasive Procedures

When conservative care fails to control pain, targeted interventions may be considered:

- Epidural Steroid Injections

Deliver anti-inflammatory medication directly around irritated nerve roots, reducing swelling and pain. - Selective Nerve Root Blocks

Used both diagnostically and therapeutically to identify and relieve specific nerve irritation.

These procedures do not cure disc pathology but can provide meaningful pain relief that allows rehabilitation to progress.

3. Surgical Treatment

Surgery is reserved for specific situations, including:

- Persistent pain lasting 6-12 weeks despite adequate conservative treatment

- Progressive neurological deficits such as worsening weakness or numbness

- Bladder or bowel dysfunction, which may indicate serious nerve compression

Common surgical options include:

- Microdiscectomy

Removes the portion of a herniated disc compressing the nerve, often providing rapid relief of leg pain. - Laminectomy

Removes part of the vertebral bone to relieve pressure on the spinal cord or nerve roots. - Spinal Fusion

Used in cases of severe degeneration or instability to stabilize affected spinal segments.

Herniated discs are significantly more likely to require surgical intervention than bulging discs, but even then, most cases still improve without surgery.

Prognosis: Bulging Disc vs Herniated Disc

- Bulging Discs

Typically remain stable over time and often never cause symptoms. When symptomatic, conservative management is usually sufficient, with an excellent long-term outlook. - Herniated Discs

Pain often improves over weeks to months as inflammation subsides and the body reabsorbs disc material. Nerve compression can prolong recovery, but the majority of patients return to normal activity with appropriate care.

Early diagnosis, symptom-guided treatment, and regular follow-up reduce the risk of chronic pain and permanent nerve damage.

Prevention Strategies

Disc problems are common, but they are not unavoidable. Long-term spinal health depends on reducing mechanical stress and supporting disc integrity.

Effective prevention includes:

- Maintaining a healthy weight to reduce spinal load

- Strengthening core and back muscles for spinal stability

- Practicing good posture during sitting, standing, and lifting

- Using proper lifting techniques, especially during heavy or repetitive tasks

- Staying physically active with low-impact exercises such as walking, swimming, or cycling

- Avoiding smoking, which accelerates disc degeneration and impairs healing

Preventive strategies become increasingly important after age 40, when natural disc degeneration accelerates.

When to See a Doctor

Medical evaluation should not be delayed if any of the following occur:

- Sudden or severe lower back pain

- Pain radiating down one or both legs accompanied by weakness or numbness

- Loss of bladder or bowel control

- Symptoms that persist or worsen after several weeks of rest and conservative care

Early medical assessment improves treatment outcomes and helps prevent long-term complications, including irreversible nerve damage.

The Bottom Line: Which Disc Causes Lower Back Pain?

Lower back pain can be frustrating and disruptive, but it’s important to remember that not all disc problems are created equal. Some abnormalities are harmless, while others demand attention. Bulging discs are extremely common and often detected incidentally on imaging; many people never experience any pain from them. Herniated discs, on the other hand, are more likely to trigger significant discomfort, nerve irritation, or even functional limitations, especially when the escaping disc material compresses spinal nerves.

Understanding the differences between these two conditions allows you to make informed decisions about treatment, lifestyle modifications, and preventive strategies, ensuring your spine remains healthy and functional over the long term.

👩⚕️ Need Personalized Health Advice?

Get expert guidance tailored to your unique health concerns through MuseCare Consult. Our licensed doctors are here to help you understand your symptoms, medications, and lab results—confidentially and affordably.

👉 Book a MuseCare Consult NowOther Blog Post You Might Like:

- Essential Guide to Lower Back, Joint, and Bone Pain: Causes, Diagnosis, and Effective Treatments

- 7 Hidden Causes of Chronic Lower Back Pain That Don’t Show on X-Rays

- Bone Pain vs Muscle Pain vs Joint Pain:7 Ways to Tell the Difference & What It Means

- Osteoarthritis vs Rheumatoid Arthritis: 7 Key Pain Patterns You Must Know

- 7 Back or Joint Pain Red Flags You Shouldn’t Ignore

- Evidence-Based Treatments for Chronic Back and Joint Pain: 21 Proven Options for Relief

Dr. Ijasusi Bamidele, MBBS (Binzhou Medical University, China), is a medical doctor with 5 years of clinical experience and founder of MyMedicalMuse.com, a subsidiary of Delimann Limited. As a health content writer for audiences in the USA, Canada, and Europe, Dr. Ijasusi helps readers understand complex health conditions, recognize why they have certain symptoms, and apply practical lifestyle modifications to improve well-being