⚠️ Affiliate Disclaimer: This post may contain affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you, if you make a purchase through one of these links. I only recommend products or services I genuinely trust and believe can provide value. Thank you for supporting My Medical Muse!

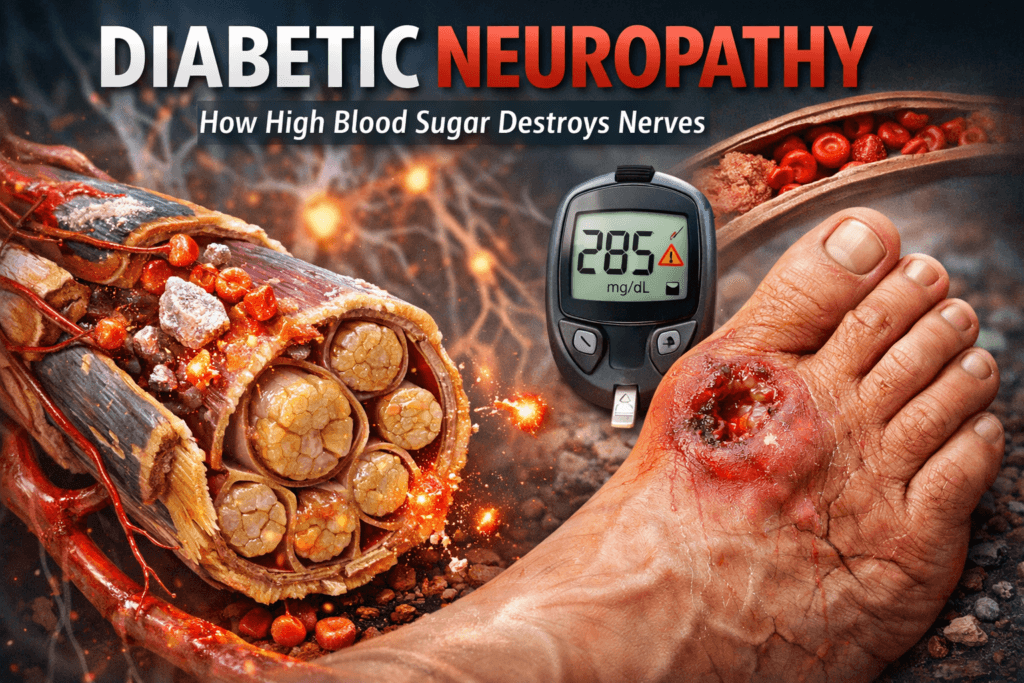

Diabetic Neuropathy Explained: 12 Brutal Reasons High Sugar Destroys Nerves

Diabetic neuropathy is one of the most devastating complications of diabetes, yet it often begins silently with no clear warning. Long before pain, numbness, or tingling set in, high blood sugar starts damaging the delicate fibers that connect brain to body. But why are nerves, more than many other tissues, so vulnerable to sugar? What makes neuropathy such a common, stubborn complication of diabetes?

This post unpacks the intricate relationship between glucose and the nervous system, revealing why nerve damage begins early, progresses relentlessly, and is often irreversible without aggressive intervention. From the biology of blood sugar to the biomechanics of nerves, we’ll explore the hidden processes that explain why diabetes is one of the leading causes of nerve dysfunction in the world today.

What Is Diabetic Neuropathy?

Diabetic neuropathy is not a single disease but a spectrum of nerve disorders caused by prolonged exposure to high blood sugar (chronic hyperglycemia). Over time, elevated glucose damages nerve fibers directly and indirectly, disrupting how signals are transmitted between the brain, spinal cord, and the rest of the body.

Unlike acute nerve injuries, diabetic neuropathy develops slowly, damage accumulates silently for years before symptoms become obvious, which is why many people already have nerve dysfunction at the time diabetes is diagnosed.

Diabetic neuropathy can affect sensory, motor, and autonomic nerves, meaning it can impair sensation, movement, and involuntary bodily functions. Virtually no organ system is immune.

The major clinical forms include:

a. Peripheral neuropathy:

This is the most common form and primarily affects the feet and legs, followed by the hands and arms. It typically begins in a “stocking-and-glove” pattern, reflecting damage to the longest nerves in the body. Symptoms often worsen at night and may progress from tingling to pain, numbness, and loss of protective sensation.

b. Autonomic neuropathy:

This form affects nerves that control unconscious functions such as heart rate, blood pressure, digestion, bladder emptying, sweating, and sexual function. Because these nerves operate in the background, damage often goes unnoticed until serious complications develop such as silent heart attacks, gastroparesis, or sudden drops in blood pressure.

c.Proximal neuropathy (diabetic amyotrophy):

This less common but severe form affects the hips, thighs, or buttocks, usually on one side of the body. It can cause intense pain, muscle weakness, and rapid muscle wasting, significantly impairing mobility.

d. Focal neuropathy:

Focal neuropathies involve sudden damage to a single nerve or nerve group, often in the face, torso, or limbs. Although frightening, many focal neuropathies improve over time, but they signal underlying metabolic and vascular injury.

Across all forms, symptoms vary but commonly include burning or stabbing pain, tingling, numbness, muscle weakness, poor balance, loss of coordination, and dysfunction of affected organs. Importantly, the absence of pain does not mean the absence of damage, numbness often reflects more advanced nerve injury.

1. Nerves Are Fragile, and Sugar Is Toxic

At the core of diabetic neuropathy is a fundamental biological mismatch: nerves are structurally delicate, metabolically demanding, and poorly equipped to handle chronic glucose overload.

Many nerve cells particularly sensory and autonomic neurons, are insulin-independent. Unlike muscle or fat cells, they do not regulate glucose entry using insulin. Instead, glucose enters these cells passively, driven solely by blood concentration. This means one thing, when blood sugar rises, nerve cells cannot protect themselves.

As glucose levels remain elevated:

- Excess sugar floods nerve cells

- Metabolic pathways become overwhelmed

- Toxic byproducts accumulate

- Cellular defenses are depleted

Over time, this constant metabolic stress injures nerve fibers, disrupts signal transmission, and impairs the cell’s ability to repair itself, because neurons have limited regenerative capacity, damage tends to accumulate rather than resolve.

This is why even moderately high glucose levels, levels that may not cause immediate symptoms can still produce long-term nerve injury when sustained over years.

2. The Polyol Pathway: A Hidden Culprit

One of the most damaging biochemical mechanisms linking hyperglycemia to nerve injury is the polyol pathway, a secondary glucose metabolism route that becomes highly active in diabetes.

Under normal blood sugar conditions, only a small fraction of glucose enters this pathway but when glucose levels rise, excess sugar is diverted into the polyol pathway, where it is converted in two steps:

- Glucose to Sorbitol (via aldose reductase)

- Sorbitol to Fructose

This shift has multiple toxic consequences for nerve cells.

- Sorbitol accumulation

Sorbitol does not easily cross cell membranes, so it becomes trapped inside nerve cells. As an osmotically active molecule, it draws water into the cell, leading to cellular swelling, structural distortion, and impaired nerve conduction. - Oxidative stress from fructose metabolism

The conversion of sorbitol to fructose increases the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). These free radicals damage DNA, proteins, and lipid membranes, key components required for nerve survival and function. - NADPH depletion and antioxidant failure

Aldose reductase consumes NADPH, a molecule essential for regenerating glutathione, the nerve cell’s primary antioxidant defense. As NADPH is depleted, glutathione levels fall, leaving nerve cells vulnerable to oxidative injury.

The combined effect is devastating, swollen cells, energy imbalance, oxidative damage, and impaired antioxidant protection all concentrated within nerve tissue.

This is why the polyol pathway is considered a central driver of diabetic neuropathy, not a secondary side effect.

3. Mitochondrial Dysfunction: The Energy Crisis

Nerve cells are among the most energy-dependent cells in the human body. Maintaining electrical gradients, transmitting impulses, and transporting materials along long axons require a constant supply of ATP, produced by mitochondria.

Chronic hyperglycemia disrupts this system at its core.

When excess glucose floods nerve cells:

- Mitochondria are forced to overwork to metabolize the surplus fuel

- Electron transport becomes inefficient

- Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated in excess

These ROS damage mitochondrial DNA, enzymes, and membranes, progressively reducing the cell’s ability to generate energy. As ATP production declines:

- Electrical signaling becomes unstable

- Axonal transport slows or fails

- Repair mechanisms shut down

- Apoptotic (cell death) pathways are activated

This energy failure is especially harmful to long peripheral nerves, such as those supplying the feet. These nerves require enormous energy to maintain signal integrity across long distances, making them the first and hardest hit in diabetic neuropathy.

In essence, hyperglycemia creates an energy crisis inside nerve cells, one that slowly suffocates function and survival from within.

4. Microvascular Disease: Choking the Nerves

Nerves do not survive on electrical signals alone. They are living tissue, and like all living tissue, they depend on a continuous blood supply.

Every nerve fiber is nourished by a network of microscopic blood vessels known as the vasa nervorum. These vessels deliver oxygen, glucose, amino acids, and repair substrates essential for nerve metabolism and regeneration. In diabetes, this lifeline is progressively damaged.

Chronic hyperglycemia injures the vascular system in several interconnected ways:

- Endothelial cell damage: High glucose disrupts the inner lining of blood vessels, impairing barrier function and triggering inflammation.

- Reduced nitric oxide production: Nitric oxide is critical for vasodilation. As its availability declines, vessels lose their ability to widen and adapt to metabolic demand.

- Capillary basement membrane thickening: Sugar-driven glycation and inflammation cause vessel walls to thicken, narrowing the lumen and reducing perfusion.

- Increased blood viscosity and sluggish flow: Elevated glucose alters red blood cell flexibility and promotes microclot formation.

The cumulative effect is nerve ischemia, a chronic state of reduced oxygen and nutrient delivery. This is not a dramatic, sudden cutoff, but a slow suffocation.

Peripheral nerves, especially those in the feet and lower legs, are the most vulnerable. They already operate at the margins of circulation. Even modest reductions in blood flow can tip the balance from maintenance to degeneration.

Over time, ischemia weakens nerve fibers, impairs repair mechanisms, and accelerates axonal loss. Once blood supply is compromised, even perfect glucose control may not fully restore nerve function.

5. Glycation: Sugar Crosslinking Nerve Proteins

Glucose is chemically reactive. When present in excess, it does more than disrupt metabolism, it physically alters the structure of proteins.

Through a process known as non-enzymatic glycation, glucose binds to proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids without enzymatic control. Over time, these early glycation products mature into advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), stable, damaging molecular crosslinks.

In nerve tissue, AGEs cause damage on multiple levels:

- Structural stiffening: AGEs crosslink collagen and other structural proteins in nerve sheaths, reducing flexibility and impairing mechanical protection.

- Disrupted axonal transport: The internal transport system that moves nutrients, enzymes, and neurotransmitters along the nerve becomes inefficient or blocked.

- Inflammatory signaling: AGEs bind to specific receptors (RAGE) on neurons, Schwann cells, and vascular cells, triggering oxidative stress and inflammatory cascades.

This process does not simply injure nerves, it locks damage in place. Glycated proteins resist normal turnover and repair, meaning the longer hyperglycemia persists, the more permanent the structural injury becomes.

AGE accumulation is one reason diabetic neuropathy progresses even when blood sugar improves late in the disease course.

6. Inflammation and Immune Dysfunction

Diabetes is not just a metabolic disease, it is a chronic inflammatory condition.

Persistent hyperglycemia activates inflammatory pathways throughout the body, including within nerve tissue and its supporting vasculature. Elevated glucose drives the release of:

- Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-alpha, IL-6, and IL-1β

- Adhesion molecules that promote immune cell attachment to blood vessel walls

- Oxidized lipids and LDL particles, which amplify vascular inflammation

This creates a state of low-grade, chronic inflammation that continuously damages nerves in two ways.

First, inflammatory mediators directly injure neurons and Schwann cells, impairing myelin maintenance and axonal integrity.

Second, inflammation worsens microvascular disease, further reducing blood flow and oxygen delivery to already stressed nerves.

Over time, immune regulation within the nervous system becomes distorted. Instead of supporting repair, immune activity becomes hostile, prolonging injury, inhibiting regeneration, and reinforcing degeneration.

This is why neuropathy often continues to worsen even in the absence of acute glucose spikes.

7. Autonomic Nervous System: The Hidden Damage

Not all nerve damage announces itself with pain. Some of the most dangerous consequences of diabetic neuropathy are silent, particularly when the autonomic nervous system is involved.

The autonomic nervous system controls vital, unconscious functions, including:

- Heart rate and rhythm variability

- Blood pressure regulation

- Gastrointestinal motility

- Bladder function

- Sexual response

- Sweating and temperature control

- Counter-regulation to low blood sugar

Damage to these nerves can destabilize entire organ systems.

Clinical consequences include:

- Gastroparesis: Delayed stomach emptying leading to nausea, bloating, erratic glucose control

- Silent ischemia and heart attacks: Loss of pain signaling masks cardiac events

- Orthostatic hypotension: Sudden drops in blood pressure upon standing, increasing fall risk

- Bladder dysfunction: Urinary retention, overflow incontinence, recurrent infections

- Sexual dysfunction: Erectile dysfunction and impaired arousal

- Hypoglycemia unawareness: Loss of warning symptoms before dangerous glucose lows

Critically, autonomic nerve damage often begins early, sometimes even before overt diabetes develops. By the time symptoms are obvious, nerve injury is usually advanced.

This makes autonomic neuropathy one of the most underdiagnosed and life-threatening complications of diabetes.

Why the Feet Are a Target: Length, Load, and Lost Feedback

Diabetic neuropathy typically begins in the feet, and this pattern is not random.

Several anatomical and physiological factors converge here:

- Length-dependent vulnerability

The nerves supplying the toes are the longest in the body. Maintaining signal integrity across such distances requires efficient axonal transport and high energy availability, both of which are impaired in diabetes. - Mechanical stress

Feet absorb constant pressure, friction, and microtrauma with every step. Healthy nerves provide protective feedback. Damaged nerves do not. - Reduced circulation

The feet are farthest from the heart and rely heavily on small vessels already compromised by diabetes-related vascular disease. - Loss of sensory feedback

As sensation declines, injuries go unnoticed. A blister, cut, or pressure point can progress into a deep ulcer without pain to prompt intervention.

This combination explains why diabetic foot ulcers, infections, and amputations are so common and so preventable when neuropathy is detected early. Foot care is not optional in diabetes. It is a frontline defense against irreversible complications.

Early Signs: Listen Before Numbness Sets In

Diabetic neuropathy does not begin with numbness. It begins with subtle disturbances that are easy to dismiss and costly to ignore.

Early warning signs often include:

- Intermittent tingling or “pins and needles”

- Burning, electric, or stabbing pain, especially at night

- Unusual sensitivity to touch or temperature

- A sensation of wearing socks or shoes when barefoot

- Mild weakness or instability in the ankles or feet

- Digestive irregularities without clear cause

- Changes in sweating patterns

These symptoms reflect functional nerve stress, not yet structural collapse. At this stage, intervention has the greatest impact. Once numbness dominates, nerve fibers are often already lost.

Listening early before sensation disappears is the difference between slowing disease and reacting to damage that is already done.

Can Nerve Damage Be Reversed?

The honest answer is uncomfortable but necessary, advanced diabetic nerve damage is rarely fully reversible. Once axons are lost and supporting structures collapse, regeneration is limited. Nerve tissue does not heal the way skin or muscle does.

However, this does not mean intervention is futile. When neuropathy is identified early before extensive axonal death, aggressive metabolic correction can meaningfully change the trajectory of the disease. Clinical evidence consistently shows that early action can:

- Slow or halt progression of nerve degeneration

- Reduce neuropathic pain and sensory disturbances

- Improve nerve conduction and functional performance

- Partially restore sensation and autonomic function in select cases

- Prevent downstream complications such as foot ulcers, infections, Charcot joints, and amputations

The cornerstone of this intervention is tight, sustained glucose control. Large, long-term trials such as the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) and the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) demonstrated that maintaining blood glucose as close to normal as safely possible significantly reduces both the incidence and severity of diabetic neuropathy. Importantly, these benefits compound over time, early control delivers long-term protection, a phenomenon known as “metabolic memory”, but glucose control alone is not sufficient.

Neuropathy is a multifactorial injury, and effective management must address all contributing pathways. Comprehensive care includes:

- Blood pressure control: Hypertension worsens microvascular ischemia and accelerates nerve injury.

- Lipid management: Elevated LDL and triglycerides contribute to vascular inflammation and oxidative stress.

- Smoking cessation: Nicotine constricts blood vessels, impairs oxygen delivery, and directly damages nerves.

- Routine foot care and neurological screening: Early detection of sensory loss prevents catastrophic complications.

- Targeted pain management: Not to cure neuropathy, but to preserve function, sleep, and quality of life while underlying damage is addressed.

Reversal, when it occurs, is partial and slow. Stabilization and preservation are far more realistic and far more achievable goals.

Experimental and Emerging Treatments

Because current therapies largely focus on symptom relief and risk reduction, significant research effort is directed toward treatments that target the root mechanisms of diabetic nerve damage.

Several approaches show promise, though most remain investigational or limited in clinical use.

- Aldose reductase inhibitors

These drugs aim to block the polyol pathway by inhibiting aldose reductase, reducing sorbitol accumulation and oxidative stress within nerve cells. Early versions were limited by side effects and modest efficacy, but newer compounds continue to be explored. - Mitochondrial protectants

Compounds such as alpha-lipoic acid target oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. Clinical studies suggest modest improvements in neuropathic symptoms and nerve conduction, particularly when used early and consistently. These agents do not regenerate nerves but may slow ongoing damage.

- AGE inhibitors and breakers

Therapies designed to prevent the formation of advanced glycation end-products or disrupt existing AGE crosslinks, aim to preserve nerve structure and vascular flexibility. While mechanistically sound, clinical translation has been slow.

Neurotrophic factors:

These include molecules like nerve growth factor (NGF) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which support neuron survival and regeneration. Delivering these safely and effectively to damaged nerves remains a major challenge.

Stem cell therapy:

Experimental studies suggest stem cells may improve nerve blood flow, reduce inflammation, and support regeneration through paracrine signaling. Human trials are ongoing, but widespread clinical use is not yet justified.

Gene therapy:

Still in early stages, gene-based approaches aim to correct metabolic pathways or enhance regenerative signaling within nerve tissue. This field holds long-term potential but remains experimental.

Despite these advances, one fact remains unchanged, no current therapy reliably reverses established diabetic neuropathy.

Until disease-modifying treatments become clinically proven and accessible, prevention and early intervention remain the most effective and most evidence-based strategy.

The window to protect nerves is early, once it closes, medicine can manage symptoms, but biology sets the limits.

Final Truth

Diabetic neuropathy is not a sudden complication, it is a slow biological failure that begins the moment glucose regulation breaks down. Nerves are engineered for rapid signaling and precision not for chronic metabolic abuse. They lack the protective mechanisms that other tissues use to buffer excess sugar, oxidative stress, and energy instability. As a result, they are among the first systems to deteriorate when glucose remains elevated.

Pain, tingling, numbness, and organ dysfunction do not appear randomly. They represent the visible endpoint of years of invisible damage, oxidative injury, ischemia, glycation, inflammation, and mitochondrial collapse occurring long before a diagnosis is made.

The idea that neuropathy is inevitable is false. What is inevitable is damage when hyperglycemia is tolerated, minimized, or detected too late. Early detection, strict and sustained glucose control, vascular protection, and full metabolic management can preserve nerve function and delay or prevent irreversible loss.

Waiting for numbness is waiting for failure, by the time sensation disappears, nerves have already died.

🌿 Your Health, Personalized

Take control of your wellbeing. Our licensed doctors at MuseCare Consult provide private, tailored guidance for your unique health needs.

✅ Book Your ConsultationMust Read:

- Diabetes Mellitus: 10 Essential Insights on Causes, Types, Symptoms, Complications, and Modern Management

- Fasting Blood Sugar vs HbA1c vs OGTT: 7 Critical Differences Every Patient Must Know

- 10 Critical Insights Into Blurred Vision in Diabetes: Temporary Changes vs Dangerous Damage

- Why Normal Blood Sugar Readings Can Still Hide Diabetes: 10 Shocking Truths You Must Know

- 7 Critical Reasons Continuous Glucose Monitoring Can Transform Your Health

- 10 Critical Insights Into Frequent Urination and Thirst in Diabetes: The Physiology Behind Classic Symptoms

- Unexplained Weight Loss or Gain in Diabetes: 11 Shocking Reasons It Happens

Dr. Ijasusi Bamidele, MBBS (Binzhou Medical University, China), is a medical doctor with 5 years of clinical experience and founder of MyMedicalMuse.com, a subsidiary of Delimann Limited. As a health content writer for audiences in the USA, Canada, and Europe, Dr. Ijasusi helps readers understand complex health conditions, recognize why they have certain symptoms, and apply practical lifestyle modifications to improve well-being