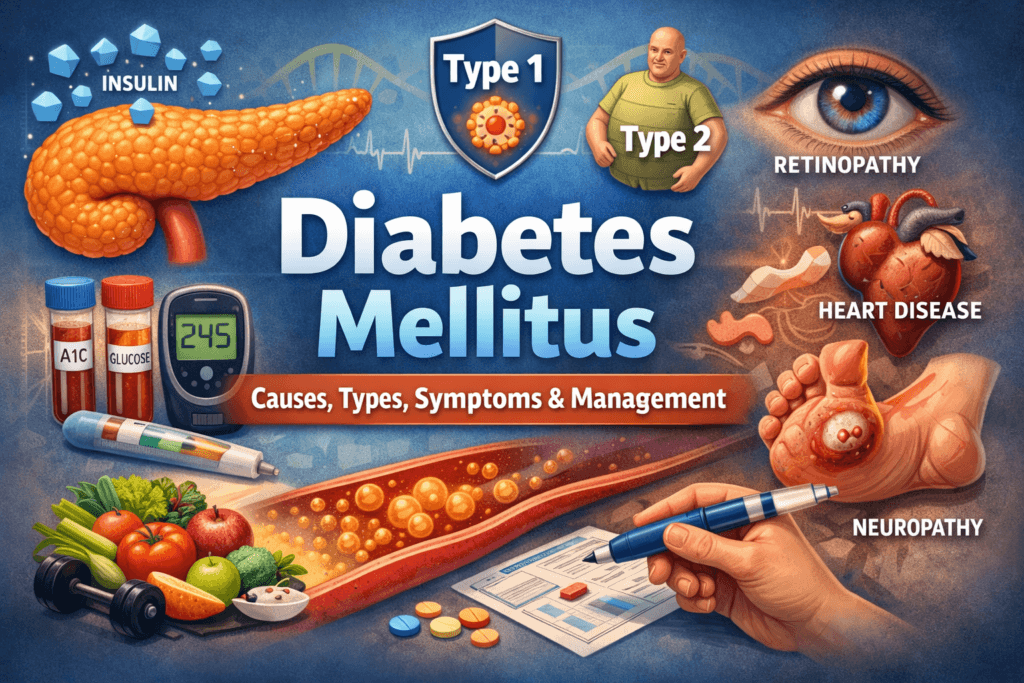

Diabetes Mellitus: 10 Essential Insights on Causes, Types, Symptoms, Complications, and Modern Management

Diabetes mellitus is one of the most misunderstood chronic conditions in modern medicine. It is often reduced to blood sugar numbers, dietary restrictions, or insulin injections. In reality, diabetes is a complex, systemic metabolic disorder that affects nearly every organ system and evolves over time.

Globally, diabetes prevalence continues to rise, not because of a single cause, but because of the interaction between genetics, environment, lifestyle, aging, and modern physiology. Despite widespread awareness, many people are diagnosed late, managed incompletely, or misled by oversimplified narratives about reversal, cures or blame-based explanations. This post exists to correct that.

What Is Diabetes Mellitus?

Diabetes mellitus is a group of metabolic disorders defined by chronic hyperglycemia persistently elevated blood glucose levels caused by defects in insulin secretion, insulin action, or both, at its core, diabetes is a disease of failed energy regulation.

Under normal physiological conditions, glucose is the body’s primary and most efficient fuel source, after a meal, carbohydrates are broken down into glucose, which enters the bloodstream. Rising blood glucose triggers the pancreas to release insulin, a hormone that acts as a biological key, allowing glucose to move from the bloodstream into cells. Once inside cells, glucose is either used immediately for energy or stored as glycogen and fat for future needs.

In diabetes, this tightly regulated system becomes disrupted, the failure can occur at multiple levels:

- Insulin may be absent or severely deficient, as in Type 1 diabetes

- Insulin may be present but ineffective, due to insulin resistance

- The timing and pattern of insulin release may be impaired, even if total insulin levels appear adequate

- Counter-regulatory hormones (such as glucagon, cortisol, and adrenaline) may overpower insulin’s effects, especially during stress, illness, or hormonal shifts

When glucose cannot enter cells efficiently, it accumulates in the bloodstream. At the same time, cells are deprived of usable energy. This creates a metabolic paradox, the blood is overloaded with fuel while tissues are functionally starving.

Over time, chronic hyperglycemia drives a cascade of pathological processes, including:

- Cellular energy stress and mitochondrial dysfunction

- Increased oxidative stress and free radical generation

- Non-enzymatic glycation of proteins and lipids

- Endothelial injury and microvascular damage

- Activation of inflammatory and immune pathways

Diabetes, therefore, is not simply a disease of high sugar. It is a systemic disorder involving:

- Hormonal dysregulation

- Mitochondrial stress

- Oxidative damage

- Endothelial dysfunction

- Immune and inflammatory signaling

While all forms of diabetes share the common endpoint of hyperglycemia, they arrive there through distinct biological mechanisms, which is why diagnosis, progression, and management vary widely between individuals.

Detailed pathophysiology of diabetes and metabolic dysfunction

Types of Diabetes Mellitus

Diabetes mellitus is not a single disease, it is an umbrella term encompassing several distinct conditions with different causes, trajectories, and management requirements. Grouping them together is clinically useful, but biologically imprecise.

Understanding the differences between diabetes types is essential for accurate diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and realistic expectations.

Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease in which the immune system mistakenly targets and destroys insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas.

Key characteristics include:

- Absolute insulin deficiency

- Onset most commonly in childhood or adolescence, but possible at any age

- Lifelong dependence on exogenous insulin

- No causal relationship with diet, lifestyle, or body weight

As beta-cell destruction progresses, insulin production declines to levels incompatible with normal metabolism, without insulin, glucose cannot enter cells, and the body shifts into a catabolic state, breaking down fat and muscle for energy. If untreated, this leads to diabetic ketoacidosis and death.

The onset of Type 1 diabetes may be abrupt, especially in children, or more gradual in adults, where it is sometimes misclassified as Type 2 diabetes initially. Regardless of age, insulin therapy is not optional, it is life-preserving.

Type 1 diabetes causes, diagnosis, and lifelong management

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

Type 2 diabetes is driven primarily by insulin resistance, combined with progressive dysfunction of pancreatic beta cells.

Key characteristics include:

- Insulin is present, particularly in early stages, but tissues respond poorly to it

- Strong genetic susceptibility influences risk

- Expression is shaped by body composition, physical activity, sleep, stress, aging, and environment

- Often develops gradually and silently over many years

In the early phase, the pancreas compensates for insulin resistance by producing more insulin. Over time, this compensatory response becomes unsustainable. Chronic metabolic stress, glucotoxicity, and lipotoxicity impair beta-cell function, leading to relative insulin deficiency.

Type 2 diabetes is the most common form globally, but it is also the most biologically heterogeneous. Two individuals with identical blood sugar levels may have very different underlying mechanisms, risks, and responses to treatment.

Type 2 diabetes mechanisms, stages, and progression

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus

Gestational diabetes develops during pregnancy due to pregnancy-related hormonal changes that induce insulin resistance beyond the body’s adaptive capacity.

Key characteristics include:

- Diagnosed during pregnancy, typically in the second or third trimester

- Caused by placental hormones that antagonize insulin action

- Usually resolves after delivery

- Significantly increases future risk of Type 2 diabetes in both mother and child

While gestational diabetes is temporary in most cases, it is not benign. Poorly controlled blood glucose during pregnancy increases the risk of fetal overgrowth, delivery complications, neonatal hypoglycemia, and long-term metabolic risk for the child.

Careful screening, monitoring, and management are essential to protect both maternal and fetal health.

Gestational diabetes risks, screening, and long-term implications

Secondary and Other Forms of Diabetes

Not all diabetes fits neatly into Type 1 or Type 2 categories. Secondary and atypical forms of diabetes are frequently underdiagnosed or misclassified.

Secondary diabetes may result from:

- Pancreatic disease, such as chronic pancreatitis or cystic fibrosis

- Endocrine disorders, including Cushing’s syndrome and acromegaly

- Medication-induced effects, particularly long-term corticosteroids and certain antipsychotics

- Genetic conditions, such as MODY (maturity-onset diabetes of the young) and neonatal diabetes

These forms of diabetes differ in cause, progression, and optimal treatment. Accurate identification matters, as management strategies effective for Type 2 diabetes may be inappropriate or ineffective for secondary forms.

Rare and secondary causes of diabetes

Why This Classification Matters

Labeling diabetes correctly is not an academic exercise. It determines:

- Treatment selection

- Timing of insulin initiation

- Risk assessment for complications

- Long-term outcomes

Understanding what type of diabetes a person has and why, is the foundation of effective, individualized care.

Insulin and Glucose Regulation: The Normal System

To understand diabetes, it is essential to first understand how glucose regulation functions in a healthy body.

Glucose is the primary fuel for most cells, its availability and use are tightly regulated to ensure a continuous energy supply while preventing toxic excess. The central regulator of this system is insulin, a hormone produced by beta cells in the pancreas and released in response to rising blood glucose levels.

The key actions of insulin include:

- Facilitating glucose uptake into muscle and fat cells

- Suppressing glucose production by the liver

- Promoting storage of excess glucose as glycogen and fat

- Inhibiting fat breakdown and ketone production

In this state, blood glucose remains within a narrow range, and cells receive the energy they need without vascular or cellular injury.

However, glucose regulation is not controlled by insulin alone. Several counter-regulatory hormones act in opposition to insulin, particularly during fasting, stress, illness, or physical exertion. These include:

- Glucagon, which raises blood glucose by stimulating liver glucose release

- Cortisol, a stress hormone that increases glucose availability

- Growth hormone, which reduces insulin sensitivity

- Epinephrine (adrenaline), which rapidly mobilizes glucose during acute stress

In health, insulin and these hormones operate in a dynamic balance, adjusting minute by minute to the body’s needs.

In diabetes, this balance is disrupted, insulin may be absent, insufficient, released at the wrong time, or overridden by insulin resistance and excessive counter-regulatory signaling. As a result, glucose control becomes unstable and unpredictable.

This explains why blood sugar levels are influenced by far more than food alone, including sleep, stress, illness, physical activity, hormonal shifts, and medications.

Read: Hormonal regulation of blood glucose explained

Symptoms of Diabetes: Early vs Late Signs

Diabetes often develops gradually and silently. Many individuals, particularly those with Type 2 diabetes remain asymptomatic for years, even as metabolic damage accumulates beneath the surface.

When symptoms do appear, they reflect the body’s response to rising blood glucose levels and impaired cellular energy use.

Early Symptoms

Early symptoms are primarily caused by hyperglycemia and osmotic effects as excess glucose spills into the urine and draws water with it.

Common early symptoms include:

- Increased thirst (polydipsia)

- Frequent urination (polyuria)

- Increased hunger (polyphagia)

- Fatigue and reduced stamina

- Blurred vision due to fluid shifts in the eye

- Unexplained weight loss (more common in Type 1 diabetes)

These symptoms are often subtle, intermittent, or attributed to stress, aging, or lifestyle factors. As a result, early diabetes is frequently overlooked or diagnosed late.

Late and Advanced Symptoms

As diabetes progresses, symptoms increasingly reflect tissue damage, nerve injury, and vascular disease, rather than glucose levels alone.

Later manifestations may include:

- Recurrent or persistent infections

- Slow wound healing

- Numbness, tingling, or burning sensations in the hands and feet

- Erectile dysfunction or reduced sexual function

- Progressive vision changes

- Chest pain, exertional fatigue, or shortness of breath

These symptoms often signal established complications, meaning the disease has been present and active for years.

Early warning signs of diabetes most people miss

Diagnosis and Testing

Diabetes is diagnosed using objective biochemical criteria, not symptoms alone. Many people meet diagnostic thresholds long before they feel unwell.

Common diagnostic tests include:

- Fasting plasma glucose, which reflects baseline glucose regulation

- Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), which assesses the body’s response to a glucose load

- Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), which estimates average blood glucose over several months

- Random plasma glucose, used in symptomatic individuals

Each test captures a different aspect of glucose metabolism and disease stage. No single test is perfect, and results must be interpreted in clinical context. Equally important is the identification of prediabetes, a high-risk metabolic state characterized by impaired glucose regulation that often precedes Type 2 diabetes. Prediabetes is not benign, it reflects early insulin resistance and increased cardiovascular risk.

Diagnosis should not end with labeling the disease. It should trigger a broader evaluation, including assessment of:

- Cardiovascular risk factors

- Kidney function

- Eye health

- Peripheral and autonomic neuropathy

- Associated metabolic conditions

Early, comprehensive evaluation allows intervention before irreversible damage occurs.

Diabetes tests explained and how to interpret results

Complications of Diabetes: Microvascular and Macrovascular

The complications of diabetes arise from chronic exposure of tissues to elevated glucose and metabolic stress. Damage accumulates slowly and often without symptoms until advanced stages. Complications are broadly divided into microvascular and macrovascular categories.

Microvascular Complications

Microvascular complications affect small blood vessels and are closely linked to long-term glucose exposure.

They include:

- Diabetic retinopathy, a leading cause of vision loss

- Diabetic nephropathy, a major cause of chronic kidney disease

- Diabetic neuropathy, which affects sensory, motor, and autonomic nerves

These complications often develop silently and progress gradually, making regular screening essential even in asymptomatic individuals.

Macrovascular Complications

Macrovascular complications involve large blood vessels and reflect accelerated atherosclerosis.

They include:

Macrovascular disease is the leading cause of death among people with diabetes. While glucose control plays a role, macrovascular risk is strongly influenced by blood pressure, lipid abnormalities, inflammation, smoking, and overall metabolic health. Effective diabetes management therefore requires a whole-system approach, not glucose control alone.

How diabetes damages blood vessels and organs

Treatment Overview: A Systems-Based Approach

There is no single treatment for diabetes, because diabetes itself is not a single disease and does not behave the same way across individuals or over time.

Effective management depends on multiple interacting factors, including:

- Type of diabetes

- Stage and duration of disease

- Age and presence of other medical conditions

- Individual physiology, risk profile, and response to therapy

For this reason, diabetes care is best understood as a systems-based, adaptive process, not a fixed plan. Across all forms of diabetes, treatment strategies are built on several core pillars:

- Lifestyle interventions, including nutrition, physical activity, sleep, and stress regulation

- Oral and injectable medications that improve insulin sensitivity, reduce glucose production, or enhance insulin secretion

- Insulin therapy, when endogenous insulin is absent or insufficient

- Monitoring and technology support, such as glucose monitoring systems and decision-support tools

These elements are combined differently for each person and adjusted as physiology, circumstances, and disease progression change. Importantly, diabetes treatment is not static. What is effective early in the disease may become inadequate later. Treatment intensity often increases over time, not because of failure or lack of effort, but because diabetes is frequently a progressive metabolic condition.

Modern diabetes care focuses not only on glucose levels, but also on reducing long-term complications, preserving organ function, and maintaining quality of life.

Modern diabetes treatments and how they work

Prevention and Reversal: Separating Science from Myth

Prevention plays an important role in diabetes, but it has limits that are often ignored or misrepresented.

Key evidence-based truths include:

- Type 1 diabetes cannot be prevented with current medical knowledge

- Type 2 diabetes risk can often be reduced, particularly through early identification and intervention

- What is commonly called “reversal” usually represents remission, not cure

- Biology sets boundaries that motivation, discipline, or willpower cannot override

In some individuals with Type 2 diabetes, sustained improvements in metabolic health can lead to normal blood glucose levels without medication for a period of time. This is best described as remission, not eradication of the disease process.

The underlying susceptibility often remains without continued metabolic support, hyperglycemia frequently returns.

Claims that diabetes can be permanently cured through diet, supplements, or mindset alone are not supported by evidence and can delay appropriate care. Such narratives oversimplify a complex disease and place unnecessary blame on patients when biology reasserts itself.

A realistic prevention framework acknowledges both modifiable risk factors and non-modifiable constraints, allowing informed action without false promises.

Diabetes prevention vs reversal, what the evidence actually shows

Living With Diabetes Long-Term

For most people, diabetes is a lifelong condition that requires ongoing attention, adaptation, and support.

Long-term management involves far more than achieving target glucose numbers. It includes:

- Psychological resilience and coping strategies

- Education, self-monitoring, and informed decision-making

- Adjusting care across life stages, from early adulthood to older age

- Recognizing and preventing treatment fatigue and burnout

- Coordinated, longitudinal medical care

Diabetes places a constant cognitive and emotional load on individuals, often requiring dozens of health-related decisions each day. Even with good control, the effort can be exhausting. Burnout is common and does not reflect weakness or noncompliance, it reflects the reality of chronic disease management, with appropriate support, realistic expectations, and adaptive care strategies, people with diabetes can live long, productive, and fulfilling lives. This is achieved not by minimizing the disease or chasing perfection, but by understanding its patterns and responding intelligently over time.

Long-term diabetes management and quality of life

Final Perspective

Diabetes mellitus is not simple, it is not a personal failure and it is not a disease that yields to shortcuts, slogans, or single-solution thinking.

Diabetes reflects a breakdown in fundamental metabolic systems shaped by genetics, physiology, environment, and time. Understanding it requires respect for biology, evidence, and complexity, not blame or oversimplification.

Knowledge alone does not cure diabetes, but ignorance reliably worsens outcomes. Delayed diagnosis, misguided expectations, and myth-driven decisions allow preventable damage to accumulate quietly over years. Clear understanding enables earlier intervention, better decisions, and more realistic long-term management.

🩺 Talk to a Health Expert Today

Personalized advice matters. Connect with licensed doctors at MuseCare Consult to review your symptoms, labs, or medications in a private, convenient session.

👉 Schedule Your ConsultOther Related Blog Post You Might Like:

- 10 Proven Benefits of Nutritional Counseling for Diabetes Management

- Can Intermittent Fasting Help Type 2 Diabetes? 9 Powerful Facts

- 10 Sneaky Symptoms of Prediabetes in Women Over 40 You Can’t Ignore

- Can Eating Too Much Fruit Daily Cause Blood Sugar Issues? 12 Surprising Facts

- Difference Between Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes: 17 Critical Biological Differences Explained

- 10 Proven Tips on How to Interpret Hemoglobin A1c Levels Accurately

Dr. Ijasusi Bamidele, MBBS (Binzhou Medical University, China), is a medical doctor with 5 years of clinical experience and founder of MyMedicalMuse.com, a subsidiary of Delimann Limited. As a health content writer for audiences in the USA, Canada, and Europe, Dr. Ijasusi helps readers understand complex health conditions, recognize why they have certain symptoms, and apply practical lifestyle modifications to improve well-being