7 Powerful Reasons Antibiotics Affect Your Microbiome Long-Term

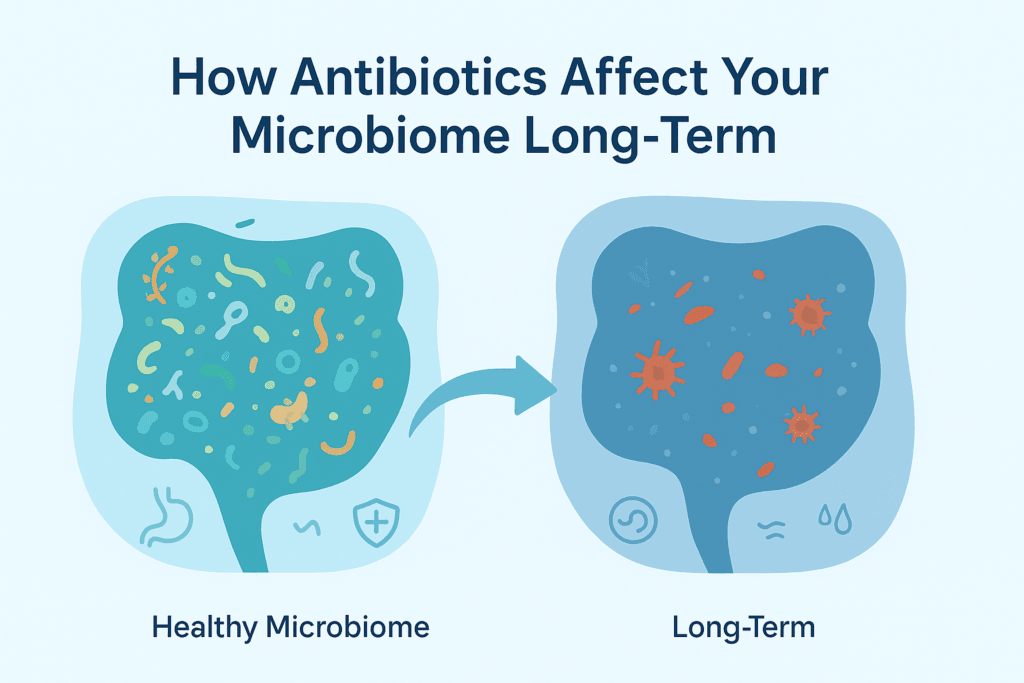

You might think taking antibiotics is a simple fix, pop a pill, kill the infection, and move on but what if that simple solution quietly rewires your body in ways you don’t notice for months or even years? Your gut microbiome, the bustling community of microbes that controls digestion, immunity, metabolism, and even mood can be profoundly affected. Even short courses of antibiotics can leave lasting footprints on this inner ecosystem.

This guide will walk you through how antibiotics reshape your microbiome, the hidden long-term consequences, and practical, science-backed steps to restore gut health after treatment.

Understanding the Microbiome: Your Inner Ecosystem

Your gut microbiome is an intricate, dynamic ecosystem made up of trillions of microorganisms including bacteria, fungi, viruses, and archaea. Together, they play an essential role in maintaining nearly every aspect of human health. When balanced, this microbial community helps to:

- Break down complex foods, converting fibers and resistant starches into energy and vital metabolites.

- Produce essential vitamins, such as B12 and K, which the body cannot synthesize on its own.

- Strengthen the gut lining, forming a protective barrier against pathogens and toxins.

- Regulate inflammation, keeping immune responses in check and reducing the risk of chronic diseases.

- Train the immune system, helping it distinguish between harmful invaders and harmless substances.

- Support metabolism and weight balance, influencing how efficiently calories are processed and stored.

- Influence neurotransmitters, including serotonin and GABA, which impact mood, cognition, and stress resilience.

A healthy microbiome is remarkably resilient, capable of bouncing back from minor disturbances. However, antibiotics, by their very nature, can disrupt microbial populations dramatically and sometimes these effects are long-lasting. Even short courses of antibiotics can leave a footprint that persists for months or years.

How Antibiotics Work and Why They Disrupt Everything

Antibiotics are designed to kill bacteria, but they rarely differentiate between harmful pathogens and beneficial microbes. This indiscriminate action can wipe out important bacterial species, particularly when broad-spectrum antibiotics are used, which target a wide range of bacteria. The result is an abrupt and significant shift in the microbiome’s composition.

Immediate Effects on the Microbiome

Within hours of starting an antibiotic course, several changes occur:

- Beneficial bacteria decline in number, sometimes dramatically.

- Microbial diversity drops, reducing the variety of species needed for a healthy gut ecosystem.

- Opportunistic bacteria, such as certain Proteobacteria, can expand and fill ecological niches left empty by beneficial microbes.

- Gut metabolites, the chemical products of microbial activity, shift in composition, affecting nutrient absorption, gut barrier integrity, and immune signaling.

Clinical studies indicate that even a single antibiotic course can reduce microbial diversity by 30-40%, a level significant enough to impact gut function. Importantly, the gut does not bounce back immediately, recovery can be slow and incomplete.

How Long Does Microbiome Recovery Take?

The timeline for microbiome recovery depends on several factors, including:

- Type of antibiotic (broad-spectrum vs. narrow-spectrum)

- Duration of treatment

- Dietary habits and fiber intake

- Age and overall health

- Baseline microbiome diversity and resilience

Research shows:

- Many microbial species begin to rebound within 2-4 weeks after treatment.

- Microbial diversity, a key indicator of gut health can take anywhere from 2 to 12 months to return to pre-antibiotic levels.

- Some critical bacterial species may never fully recover, especially after repeated courses.

- Early-life antibiotic exposure can lead to permanent microbiome shifts, with implications for immune and metabolic health.

In adults, the microbiome is generally more stable, but frequent antibiotic courses, two, three, or more per year can result in chronic microbial depletion and long-term imbalance.

The Five Biggest Long-Term Effects of Antibiotics on the Microbiome

Antibiotics are lifesaving, but their downstream effects on the gut microbiome can be profound. Here are the five most significant long-term consequences:

1. Loss of Microbial Diversity

Diversity, the number of distinct microbial species present is widely recognized as the strongest indicator of microbiome health. Antibiotics often reduce this diversity, which is critical because each species plays a unique role in maintaining digestive, immune, and metabolic function.

Loss of microbial diversity can disrupt:

- Fiber breakdown, reducing the production of beneficial short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).

- Gut barrier protection, making the intestines more permeable to pathogens and toxins.

- Immune training, impairing the body’s ability to respond appropriately to infections and allergens.

- Nutrient absorption, limiting the availability of vitamins and minerals essential for health.

Long-term consequences of low diversity include:

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

- Obesity and metabolic disorders

- Type 2 diabetes

- Food sensitivities

- Chronic systemic inflammation

Restoring microbial diversity after antibiotics takes time, diet, lifestyle changes, and sometimes targeted supplementation.

2. Overgrowth of Opportunistic Bacteria

When beneficial bacteria are reduced, ecological niches open up, allowing opportunistic bacteria and yeast to proliferate. This imbalance, known as dysbiosis, can persist long after the antibiotics are stopped. Common consequences include:

- Bloating and gas

- Irregular bowel movements (constipation or diarrhea)

- Fatigue and brain fog

- Food intolerances and sensitivities

- Yeast overgrowth, such as Candida

- Increased intestinal permeability, contributing to “leaky gut”

Certain pathogenic bacteria, such as Clostridioides difficile, can take advantage of a weakened microbiome, sometimes causing serious infections without intervention, dysbiosis can remain chronic, creating ongoing digestive and systemic issues.

3. Reduced Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)

Beneficial gut bacteria produce essential compounds called short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including acetate, propionate, and butyrate. These molecules are not just byproducts, they play critical roles in maintaining gut and overall health:

- Nourish colon cells: Butyrate is the primary fuel for the cells lining the colon, promoting a healthy gut barrier.

- Reduce inflammation: SCFAs help regulate immune responses and limit chronic inflammation.

- Support immune function: They modulate immune cells, improving defense against pathogens.

- Regulate appetite and satiety: SCFAs influence hormones like leptin and GLP-1, impacting hunger and food intake.

- Maintain insulin sensitivity: SCFAs improve glucose metabolism, helping prevent metabolic dysfunction.

Antibiotics can dramatically reduce SCFA-producing bacteria, such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Roseburia. Low SCFA levels are associated with:

- Leaky gut, allowing toxins and undigested food particles to enter circulation.

- Metabolic dysfunction, including impaired glucose regulation and fat metabolism.

- Mood changes, as SCFAs influence neurotransmitter production.

- Chronic inflammation, increasing long-term disease risk.

Restoring SCFA levels can take weeks to months, depending on diet, probiotic support, and overall microbial recovery.

4. Increased Risk of Digestive Disorders

Antibiotics are a known risk factor for several long-term gastrointestinal issues. When the gut microbiome is disrupted, normal digestive functions can be compromised:

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

Research indicates that up to 25% of IBS cases may develop after an infection or antibiotic exposure. Dysbiosis can trigger chronic gut hypersensitivity, bloating, and irregular bowel movements.

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO)

Antibiotics can disrupt gut motility and microbial balance, allowing bacteria to migrate into the small intestine. This overgrowth leads to gas, bloating, diarrhea, or malabsorption of nutrients.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

Studies suggest that childhood antibiotic exposure may increase the risk of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis later in life. The microbiome guides immune system development, and early disruption can predispose the gut to inappropriate inflammatory responses.

5. Altered Metabolism and Weight Regulation

The gut microbiome plays a central role in how calories are extracted and stored from food. Antibiotics can disrupt this delicate balance:

- Unintentional weight gain: Some individuals gain weight after antibiotic exposure because microbiome shifts favor energy-harvesting bacteria.

- Weight loss: In other cases, depletion of key bacterial species impairs nutrient absorption, leading to unintentional weight loss.

- Childhood obesity risk: Early-life antibiotic exposure has been consistently linked to higher rates of obesity later in childhood.

The microbiome’s influence on metabolism underscores why restoring balance is essential after antibiotic use.

Do Some Antibiotics Cause More Damage Than Others?

Yes. Broad-spectrum antibiotics have the most profound and lasting effects because they target a wide array of bacteria:

High Impact

- Ciprofloxacin

- Clindamycin

- Amoxicillin-clavulanate (Augmentin)

- Azithromycin

- Clarithromycin

- Cephalosporins

These medications can cause long-lasting depletion of beneficial bacteria.

Moderate Impact

- Amoxicillin

- Penicillin

- Doxycycline

These are disruptive but generally allow for faster recovery of microbial diversity.

Lower Impact

- Narrow-spectrum antibiotics

- Targeted antibiotics for specific pathogens

Even these can reduce microbial populations, so caution is warranted.

Antibiotics in Infancy and Childhood: Effects That Can Last Years

Early childhood is a critical window for microbiome development. Antibiotic exposure during the first three years of life can have long-term consequences:

- Alter immune development, affecting how the body responds to infections and allergens.

- Increase risk of allergies and asthma, likely due to immune dysregulation.

- Increase susceptibility to eczema, a marker of altered immune-microbiome interactions.

- Influence weight and metabolism, contributing to childhood obesity.

- Reduce microbial diversity for years, sometimes permanently altering gut composition.

While adults are more resilient, repeated antibiotic exposure across a lifetime still has cumulative effects on gut health.

Symptoms of a Post-Antibiotic Microbiome Imbalance

After completing antibiotics, you may notice both digestive and systemic symptoms, often subtle but persistent:

Digestive symptoms

- Bloating and gas

- Diarrhea or constipation

- Food sensitivities

- Acid reflux or heartburn

Systemic symptoms

- Fatigue or low energy

- Brain fog or difficulty concentrating

- Lower stress tolerance

- Increased anxiety

- Sugar cravings

- Skin flare-ups (eczema or acne)

These symptoms reflect reduced microbial diversity and imbalance, signaling the need for targeted recovery strategies.

Can the Microbiome Fully Recover? Yes, But It Takes Strategy

The microbiome is adaptable and resilient, but recovery is not automatic. The first 8-12 weeks after antibiotic treatment are critical for long-term restoration. Evidence-backed strategies include:

- Reintroducing fiber-rich foods gradually to feed beneficial microbes

- Incorporating fermented foods and probiotics to repopulate the gut

- Avoiding ultra-processed foods that promote dysbiosis

- Supporting SCFA production with prebiotic foods and resistant starches

- Prioritizing sleep, stress management, and regular physical activity

The actions you take during this period can determine whether your microbiome fully recovers or remains compromised, influencing digestive, immune, and metabolic health for months or years.

How to Support and Rebuild Your Microbiome After Antibiotics

The gut microbiome is resilient but not indestructible. After antibiotic use, intentional steps are necessary to restore balance, diversity, and function. The first 8-12 weeks post-antibiotic are critical for recovery, and the following strategies are evidence-based ways to rebuild your gut ecosystem.

1. Reintroduce Fiber Gradually but Consistently

Fiber is the primary fuel for beneficial gut microbes. After antibiotics, reintroducing a variety of fiber-rich foods is one of the fastest ways to rebuild microbial diversity.

Aim for a wide range of sources, including:

- Vegetables: leafy greens, broccoli, carrots

- Fruits: berries, apples, pears

- Legumes: lentils, chickpeas, black beans

- Whole grains: oats, quinoa, barley

- Nuts and seeds: almonds, chia, flax

Key tips:

- Increase fiber slowly if your gut is sensitive; sudden spikes may cause bloating or gas.

- Focus on diversity rather than sheer quantity, feeding a broad spectrum of microbes is more important than consuming massive amounts of a single type of fiber.

2. Add Fermented Foods Regularly

Fermented foods naturally introduce beneficial bacteria back into the gut. Incorporating these into your daily diet can accelerate microbiome recovery.

Recommended fermented foods:

- Yogurt and kefir

- Sauerkraut and kimchi

- Miso and tempeh

- Fermented pickles (avoid vinegar-based)

- Kombucha (limit if sensitive to histamines)

Research insights:

Some studies suggest that fermented foods may increase microbial diversity even more effectively than fiber alone, especially in people recovering from antibiotic exposure.

3. Use Targeted Probiotics Wisely

Probiotics can be an important tool for restoring balance, but not all strains are equally effective. The best evidence supports these post-antibiotic strains:

- Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG

- Bifidobacterium longum

- Bifidobacterium lactis

- Lactobacillus plantarum

- Saccharomyces boulardii (a probiotic yeast, particularly effective in preventing antibiotic-associated diarrhea)

Guidelines for use:

- Take probiotics 2 hours apart from antibiotics if still on treatment.

- Continue for 2-8 weeks after completing antibiotics to support microbiome recovery.

4. Focus on Prebiotic-Rich Foods

Prebiotics are non-digestible fibers that feed beneficial bacteria, helping them grow and restore balance. Excellent sources include:

- Garlic, onions, leeks

- Asparagus, Jerusalem artichokes

- Slightly green bananas

- Oats and barley

- Chicory root and flaxseed

Start with small amounts (e.g., 1 tablespoon of cooked prebiotic food) if your gut is sensitive to prevent bloating or discomfort.

5. Avoid Ultra-Processed Foods for 2-4 Weeks

Highly processed foods can undermine microbial recovery, feeding inflammatory bacteria while reducing diversity. Minimize:

- Packaged snacks and sugary beverages

- Preservatives and artificial additives

- Artificial sweeteners, particularly sucralose

Instead, focus on whole, nutrient-dense foods, which provide both fiber and phytonutrients that support beneficial bacteria.

6. Consider Postbiotics for Gut Lining Repair

Postbiotics are metabolic byproducts of bacteria, such as butyrate, propionate, and acetate, which help repair the gut lining and reduce inflammation. You can support postbiotic activity by:

- Consuming high-SCFA fibers such as resistant starches (e.g., cooked and cooled potatoes or rice, green bananas)

- Considering butyrate supplements under professional guidance

Postbiotics play a critical role in healing intestinal cells and maintaining a robust barrier against pathogens.

7. Prioritize Sleep and Stress Management

Sleep deprivation and chronic stress alter gut microbial composition in ways similar to antibiotics. Supporting your microbiome includes:

- 7-9 hours of quality sleep per night

- Mindfulness practices or breathing exercises to manage stress

- Regular physical activity, which has been shown to positively influence microbiome diversity

Lifestyle factors directly shape microbial recovery and enhance the benefits of dietary interventions.

Special Considerations: What If You Need Frequent Antibiotics?

Some individuals require repeated courses of antibiotics for conditions such as:

- Chronic infections

- Recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs)

- Sinus infections

- Acne treatments

- Post-surgery prophylaxis

If this applies to you:

- Work with a doctor to narrow the antibiotic spectrum where possible.

- Support your microbiome during treatment, with probiotics and fiber.

- Strengthen immune function naturally through diet, sleep, and lifestyle.

- Explore alternatives where appropriate, such as targeted therapies or preventive strategies.

- Commit to long-term gut rebuilding, including consistent prebiotic and probiotic intake.

In these cases, prevention is essential, protecting the microbiome before, during, and after antibiotics is critical for long-term health.

When to Seek Professional Help After Antibiotics

Consult a healthcare provider if you experience:

- Digestive issues persisting for more than 4-6 weeks

- Persistent bloating, abdominal pain, or diarrhea

- Unexplained fatigue or systemic symptoms

- New food intolerances

- Suspected SIBO

- Recurrent yeast infections or thrush

Sometimes, targeted testing and professional guidance are needed to restore the microbiome fully, especially after repeated or broad-spectrum antibiotic use.

Can Antibiotics Ever Be Good for the Microbiome?

Interestingly, antibiotics can have indirect benefits for gut health when used appropriately. For example, they may:

- Eliminate pathogens causing chronic inflammation

- Clear bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine

- Resolve chronic infections that disrupt immune and microbial balance

The key is appropriate, targeted use rather than indiscriminate avoidance. When guided by a healthcare professional, antibiotics can improve the microbiome indirectly by removing harmful bacteria and allowing beneficial species to flourish.

Final Thoughts: Restoring Balance After Antibiotic Use Is Possible and Crucial

Antibiotics are lifesaving, but they leave a mark on your gut that can last longer than most people realize. The good news? Your microbiome is resilient, and with deliberate action, you can guide it back to health.

The key is intentional recovery, support your gut while taking antibiotics, rebuild microbial diversity afterward, and adopt habits that strengthen your microbiome over the long term. This isn’t about perfection, it’s about consistency. Small, targeted steps in diet, lifestyle, and supplementation add up, helping you restore a thriving gut ecosystem, protect your immunity, and improve overall well-being.

Remember, the microbes in your gut are not passive, they respond to how you treat them. Nourish them wisely, and they will repay you with better digestion, immunity, and energy.

👩⚕️ Need Personalized Health Advice?

Get expert guidance tailored to your unique health concerns through MuseCare Consult. Our licensed doctors are here to help you understand your symptoms, medications, and lab results—confidentially and affordably.

👉 Book a MuseCare Consult NowRecommended Blog Post:

- 15 Shocking Ways Low-Grade Inflammation Is Sabotaging Your Health

- 12 Low-FODMAP Mistakes That Sabotage Gut Health (and How to Avoid Them)

- How to Stop Gas After Eating Beans: 12 Proven Ways to Prevent Bloating

- 12 Powerful insights Into What Your Diet Really Needs (micronutrients and Supplements)

- 7 Shocking Risks of Too Much Protein for Non-Athletes: What You Must Know

Dr. Ijasusi Bamidele, MBBS (Binzhou Medical University, China), is a medical doctor with 5 years of clinical experience and founder of MyMedicalMuse.com, a subsidiary of Delimann Limited. As a health content writer for audiences in the USA, Canada, and Europe, Dr. Ijasusi helps readers understand complex health conditions, recognize why they have certain symptoms, and apply practical lifestyle modifications to improve well-being